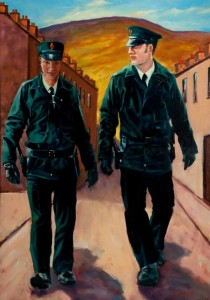

Image: C.E.M.J Pailpoint, Two Royal Ulster Constabulary Officers (2000s)

More information about this painting here.

Excerpts from “Northern Ireland: The Plain Truth”

“At the first Londonderry Civil Rights march the Royal Ulster Constabulary sealed off the marchers in Duke Street in front and behind and batoned them indiscriminately. Gerry Fitt, M.P., was wounded on the head. Edward McAteer, M.P., in the groin. A girl was batoned on the mouth. The people were hosed with water cannons. This was all witnessed by two British labour M.P.’s, John Ryan and Mrs. Anne Kerr. While this was going on, police not actively engaged were laughing.” (Minister of Home Affairs – Mr. William Craig) [1]

“At a later date student marchers at Burntollet Bridge received scant protection from the R.U.C. who fraternised freely with the Paisleyites led by Major Bunting. Students were stoned, beaten with nail-studded clubs, and thrown into a stream. Threats of rape were made on the women.

In January 1969, police, some alleged to be intoxicated, broke into houses in Lecky Road, Derry, and, using obscene and sectarian abuse, attacked the citizens indiscriminately with batons and kicks. As a result, 190 formal complaints against the police were documented.

Again, demonstrating its particular brand of ‘democracy’ the Ulster Government ordered an Enquiry to be carried out by, police officials themselves! The Government has refused to make the results of this Enquiry public.” (Minister of Home Affairs – Capt. William Long) [2]

“In April 1969, in Derry, the police were caught at a disadvantage and were stoned by a mob and some injured. Police later invaded Catholic homes and rendered many men, women (including a semi-invalid) and children hospital cases!” (Minister of Home Affairs – Mr. R. Porter) [3]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3TzmULzLuw

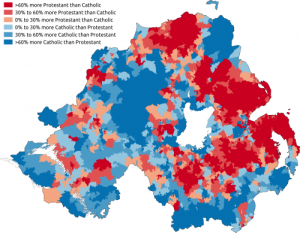

At the heart of the policing issue lies demographic underrepresentation. In 1969, there was approximately 1.5 million people living in Northern Ireland, of whom one-third (~.5 million) were Catholic and two-thirds (1 million) were Protestant.[4] Nevertheless, Catholics were severely underrepresented in virtually every facet of government; however, this underrepresentation was especially prominent in the realm of policing.

Images: Distribution of Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland

The primary police agency in Northern Ireland was the Royal Ulster Contabulary (R.U.C.). In 1969, the R.U.C. was comprised of around 3,000 members, of which only 10% (~300) were Catholic. Of 50 Officers in the R.U.C., only six were Catholic.[5] This indicates that there was roughly a 20% disparity in representation for Catholics among the police as compared to the civilian population.

Image: Flag of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (R.U.C.)

There was an additional police force in Northern Ireland known as the Ulster Special Constabulary, or ‘B-Specials’. “This [was] a sectarian part-time force 11,300 strong. All members are Protestant. They are mainly recruited from members of the Orange Order.”[6] So, not only were Catholics severely underrepresented within the R.U.C., they had to contend with a separate, exclusively Protestant police force that had extremely strong Unionist ties and had the right to retain private weapons. Catholics did not have the right to keep weapons in their homes under the provisions of the 1922 Special Powers Act.

Image: B-Specials

The 1922 Special Powers Act gave the R.U.C. and the ‘B-Specials’ an unbelievable amount of latitude in determining how to police their respective districts and jurisdictions. While the Special Powers Act contained many provisions, the large majority of this legislation was designed to specifically target and disadvantage Catholics. One shining example of this can be seen in Section 3, subsection 1, which states:

“The civil authority may make orders prohibiting or restricting in any area: (a) The holding of or taking part in meetings, assemblies (in eluding fairs and markets), or processions in public places; (b) The use or wearing or possession of uniforms or badges of a naval, military or police character, or of uniforms or badges indicating membership of any association or body specified in the order; (c) The carrying in public places of weapons of offence or articles capable of being used as such, (d) The carrying, having or keeping of firearms, military arms, ammunition or explosive substances; and, (e) The having, keeping, or using of a motor or other cycle, or motor car by any person, other than a member of a police force, without a permit from the civil authority, or from the chief officer of the police in the district in which the person resides.”[7]

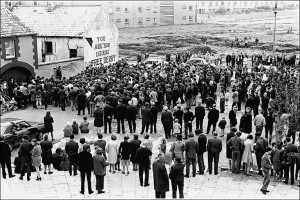

Image: A crowd gathers at Free Derry wall for a civil rights march

Taken in context, it is not hard to see how the Special Powers Act completely disenfranchised Catholic citizens of Northern Ireland and left them to literally fend for themselves. The combination of underrepresentation in the R.U.C. and the existence of the B-Specials meant that the restrictions set forth by the civil authority under the Special Powers Act primarily affected Catholic neighborhoods such as Derry’s Bogside. The Special Powers Act gave the police undue discretion in determining what to do when Catholics violated its provisions, such as gathering to have a meeting.

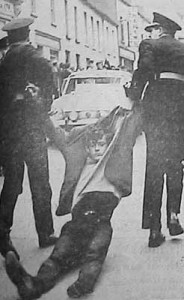

Image: A protestor is dragged away by R.U.C. constables

Hopefully, this introduction has shed some light on the conditions in Northern Ireland in 1969 and how these conditions created a tense and volatile climate that contributed significantly to civil rights abuses during the years preceding Bloody Sunday, and played a direct role in the tragic events that took place that fateful day.

[1] Northern Ireland: The Plain Truth. Second Edition. Castlefields, Dungannon: The Campaign for Social Justice in Northern Ireland, 1969. Print.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid, p. 1.

[5] Ibid, p. 7.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Fionnuala McKenna. “Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland), 1922.” Conflict Archive on the Internet. CAIN Web Service. Web. 1 December 2014. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/spa1922.htm.

Roadmap

One Reply to “Policing in Northern Ireland: The Plain Truth (1969)”