Learning about Irish history, and encountering the visible results of that history on our trip to Ireland, I noticed that there were many substantial events and themes that involve walls. Walled cities, houses that form walls along the street, walled Victorian gardens, architecture that encloses buildings, separates spaces between classes, walls erected in war or in defense, Ireland has a history entangled with walls and boundaries. On our trip from Galway to Dublin to Derry to Sligo, every town or city, every castle or garden, had some physical trace of Ireland’s history of conflict, partition, and separation. In Derry, for instance—a city at the center of the conflict between Catholics and Protestants and Great Britain, looking at the city’s walls was to look at the physical embodiment of the history of violence and failed policies of the place—to tell the story of the walls is to tell of the history of the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland.

Likewise, to observe the walls of Ireland, in any sense, is to observe the boundaries that come up in its history and persist into the present day, and to observe how those boundaries have been permeated as conflicts begin to resolve and change. Ireland’s particular history of divisions between classes, religions, generations, and regions (to name a few) give walls certain significance in Ireland. That is not to say that all walls in Ireland have a broad historical meaning and connections to larger issues, but simply that there are many walls in Ireland that carry historical weight, and that it will be useful to our understanding of Irish history, I hope, to take a close look at these physical boundaries that exist today in Ireland.

Sites of Opposition in Derry

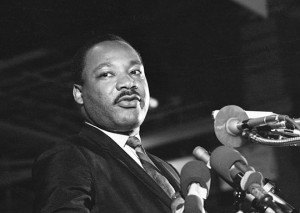

In Derry, Northern Ireland, the walls provide the most obvious key to the history of the landscape, with central areas of the city painted with very visible reminders of the centuries of sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants and Great Britain—starting with plantation in the mid 1600s, and capped off by the Troubles in the late 20th century. Derry is a walled city on a hill—a defensive settlement, protecting English colonizers from the Irish they were attempting to colonize. According to R.F. Foster, in Modern Ireland,

“In theory, the six counties of Armagh, Colerain, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Cavan and Donegal were to be worked on, producing an ideal pattern of close settlement that would feature urbanization and segregation…Chief undertakers would be allowed 3,000 acres, on condition that they were resident, settled English or Scottish families, and undertook to bear arms and build defenses.” (61)

Essentially, the new landowners, forcing land from the Irish, set up a feudal system under plantation, in which they’d plant themselves on Irish land, take the native Irish as tenants, and extract their labor for profit. The dispossession of the Irish created widespread resentment, and an unstable social and economic order that for years created unrest and injustice.

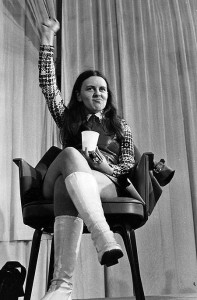

The walls in Derry tell the story of this unrest and injustice—both the Protestant walls making up the city center and the murals walls of the homes in the Catholic district outside of the city walls tell the story of sectarian conflict and opposition, and attempts at peace after the Troubles. During the Troubles, beginning in the late 60s, the Bogside neighborhood in Derry was the site of fierce conflict between Catholics—who had been denied basic civil rights like representation in government, opportunity for housing, and the right to assembly and free speech—and Unionists, who were the minority party holding the majority of power. In order to encourage peace in the increasingly sectarian conflict, a group of artists took to the walls of homes in the Bogside, and painted murals to discourage violence and oppose anti-Catholic violence from Unionist government and police force. The murals often face the Protestant walled city, and they can all be seen from atop the city walls, as if looking into the Bogside, the conflict looks back.

The murals that decry sectarian violence and British occupation are all visible from the city walls, making the walls not only protests for peace, but spaces of non-violent but aggressive opposition, intruding into the daily lives of those who walk the walls and live above the Bogside neighborhood.

The Protestant walls themselves are also visible sites of conflict. Built during the plantation period, the walls were designed as defenses for the English and Protestant undertakers of colonization. According to R.F. Foster, “The famous walls of Derry were completed in 1618 after four years of building, making it one of Ireland’s principal fortresses…Catholics were not allowed to settle inside Derry, as a threatening majority; they colonized the Bogside outside the walls” (74). The segregation imposed under plantation remained, and though today the walls have become open to all, evidence of sectarianism remains entrenched. The houses behind the walls, on the Protestant side, have metal screens in front of their windows to prevent projectiles thrown from the Bogside from breaking their windows. The towers interspersed between the walls are splashed with paint, and the wall that overlooks the Bogside is spray painted “End British Internment,” in opposition to British imprisonment of IRA members.

The walls of Derry illustrate the continuing results of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, showing the history of the conflict in murals and on the Protestant walls. Though the Troubles have arguably ended, and Northern Ireland is coming closer to reconciliation, Derry’s walls tell of a history of sectarianism and violence, separation and exclusion, and allow us to see evidence of those conflicts continuing into the present.

Architecture of Division

Much of the architecture constructed by the Irish upper class in the 18th century has remained until the present day in Ireland. The ascendancy architecture illustrates attempts to divide the population, to create insides and outsides, to create walls in society in order to maintain the ascendancy position of power over a majority poor Catholic lower class. Castles, government buildings, public housing, estates, and gardens were all built by upperclass Irish Protestants (the ascendancy) in order to make sure their landscape enforced the ascendancy’s power, and reached toward their aspirations toward British social status. Row houses in Dublin, the Irish parliament building, colleges, parks, and bank buildings, were all designed by ascendancy landholders and officials, in order to include members of the ascendancy and exclude Irish Catholics and lower classes.

According to R.F. Foster, the ascendancy, or the Anglo-Irish, of the 18th century saw themselves as “a social elite, professional as well as landed, whose descent could be Norman, Old English, Cromwellian or even (in very few cases) ancient Gaelic. Anglicism conferred exclusivity, in Ireland as in contemporary England; and exclusivity defined the Ascendancy, not ethnic origin. They comprised an elite who monopolized law, politics and ‘society’, and whose aspirations were focused on the Irish House of Commons” (170). The Anglo-Irish, then, saw themselves as the elite of Irish society, and built in order to enforce that exclusivity that they believed their Anglicism conferred. The evidence of this exclusivity is still visible in Ireland today, particularly in “Georgian Dublin,” and ascendancy estates in rural areas.

Georgian Dublin

In Dublin, Georgian architecture–a style that ruled throughout the reign of the four Georges over the England–creates a sense of exclusive spaces, of insides and outsides, noble and peasant, creating both a sense of grandeur and nobility for the Anglo-Irish, while intimidating and excluding lower class Irish Catholics.

Trinity College in Dublin, as the seat of Anglo-Irish intellectualism from early in Ireland’s history of colonization, was firmly within the grasp of the ascendancy, reflecting their aesthetics and their aspirations. The college is built like a fortress, the buildings’ walls surround a central green with manicured grass upon which one is not allowed to step, and the only entrance to the green is two people wide, creating an exclusive space within and Anglo-Irish ethos that remained even once enrollment was allowed for Irish Catholics.

Colleges reminiscent of Trinity were built across Ireland as Anglo-Irish centers for education, status, and exclusivity, and following the same style of the green protected by outer walls, with a small entrance, creating a sense that the interior of the school is walled off to common Irish Catholics.

Row houses in Dublin also create boundaries between the public and the ascendancy life. The houses appear identical, side by side, not separated by alleys or walls–from the street they appear as one unified wall running along the road. The residences at Merrion Square in Dublin, still an upperclass area of the city, are a fine example of the facade that Georgian row houses create, as they create the illusion of a united front of ascendancy landowners.

In Dublin, the former and current buildings that house parliament also create the illusion of aristocratic grandeur and exclusivity. As the Anglo-Irish in Dublin competed for seats in parliament prior to the Acts of Union in 1801, which abolished Irish parliament altogether, they formed a sort of ascendancy social club in the Irish House of Commons, which provided a stage for ascendancy politicians. According to Foster, “The Irish high style of parliamentary rhetoric was celebrated: a language of baroque metaphor and personification, punctuated by brutal rejoinders. The most business-like debates were far less well attended than those which permitted lofty attitudinizing” (234). The inclusivity for Anglo-Irish members of the House of Commons, and the exclusivity for Catholics and lower classes, is well reflected in the architecture of the parliament buildings.

Big Houses and the Controlled Landscape

Big Houses, built in rural Ireland by Anglo-Irish landlords beginning in the 18th century, represent another attempt to create walls between classes, and to control the landscape of the countryside. According to Foster, “That Ascendancy desire to build and to plan deserves some attention: it may indicate an obsession with putting their mark on a landscape only recently won and insecurely held” (193). The ascendancy built imposing structures in the countryside, in order to mark their landscape as their own and, as Foster explains, to create the illusion of their ancient roots in Ireland: “…the larger Irish houses were treated to castellation and gothicizing…the Ascendancy built in order to convince themselves not only that they had arrived, but that they would remain” (194). Indeed, the Big Houses of the Anglo-Irish betray attempts at looking fortified and ancient, as well as opposed to the land upon which they sat. Big Houses create walls between the Anglo-Irish culture within, and peasant life without, the backs of whom which the Anglo-Irish culture rested.

Glenveagh Castle, one of many responsible for brutal evictions during the famine period, is one of the increasingly few Big Houses that is not presently in decline. Glenveagh is maintained and curated by the state, taking in tourists all year long, boasting well-kept and expanding gardens, and well-furnished rooms. On our tour of Glenveagh, the introduction video and the guides glossed over the evictions that made it possible for the castle and gardens to be built, and made sure to point our the wealth on display at the castle, which alludes to the fact that the allure of opulence still holds sway to those who come to see these castles, and that there remains a divide between historical fact and the world of the ruling class. The castle itself presents a harsh exterior to the surrounding landscape and to the tenants that once lived there, exuding authority as it rises up from in front of the water.

The estate at Strokestown was different, and presented a more contextualized view of the history of the famine, without so much veneration of wealth. The estate is now home to Ireland’s national famine museum, and was the site of brutal evictions of thousands of Irish tenant farmers during the famine. Inside the museum, displays take you through the history of the famine, and the history of the famine and evictions at Strokestown itself, doing much to erode the walls built between the desolation and violence that allowed the Anglo-Irish to occupy thousands of acres of estates.

Walled Gardens

At each estate we visited, we were privy to a tour of the walled Victorian gardens, which allowed us to see how the landowners attempted to mark and control the physical landscape around them. At Strokestown, the walled garden was in decay, but slowly being restored. Still, the garden was only accessible by code, which you had to retrieve from a tour guide, and it was being restored to a Victorian style, which, even in its remnants at Strokestown, visibly sought to change the landscape into straight lines, manicured grasses and hedges, and private areas for aristocratic leisure. The walls themselves separated the garden from the surrounding landscape, which, prior to their evictions, contained tenant farmers upon whose labor these estates and gardens were built.

The gardens at Strokestown and Glenveagh did have certain aspects that subverted the walled, controlled aesthetic. At Strokestown, the woods next to the garden wall contained a walk of folk and childrens’ art, which celebrated Ireland’s mythology and natural landscape, instead of attempting to control the landscape and hide the peasantry from view. At Glenveagh as well, recent developments in the garden, headed by a very passionate gardener, have seen the garden turn from a walled and controlled artificial landscape into a garden that attempts to work itself into the natural landscape, and to celebrate the natural flora and fauna of Ireland. Both exterior gardens represent a turn away from the ascendancy penchant for creating boundaries between the landscape and its people, and toward permeating those walls, and celebrating the landscape and its people.

Works Cited

Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland, 1600-1972. New York, N.Y.: Penguin, 1989. Print.

Tour by the Bogside Artists, Derry.

Tours in Glenveagh castle and Strokestown Estate.