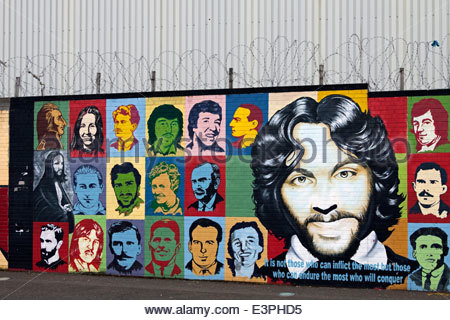

When considering the Irish body as a piece of text, we see that the same marker can be used to identify a person as either part of an in-group, meaning that they belong to a shared identity, or an out-group, meaning that they do not. In the case of forcible mortification done to a person in disregard of their will, the person is marked by the opposite group as being separate from their in-group. Whereas uniforms serve as a visible, freely-chosen marker of in-group inclusion (see the IRA uniformed soldiers below), the body serves as a more permanent and inalienable canvas for such messages to take place.⁹

Sociological studies commonly identify in-groups and out-groups as a method of social control wherein acceptable behavior is defined and continuously reaffirmed based on adherence to a set of shared beliefs.¹ Applying this to the legacy of the 1916 Easter Rising, we see a legacy of retributive justice enacted in Northern Ireland by both Catholic groups like the IRA as well as from the Protestant majority.⁴ These penal acts serve to mark opposing groups as having violated the aggressors’ belief system, as well as to physically disable the victim so that they will understand going against the group as having an impact on the appearance and agency of their bodies.

In contrast, elective body modification and mortification, such as tattooing and hunger striking, seek to mark one’s insider status within their selected group through deliberate creation of a spectacle meant to have a visual impact. For example, Lord Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney’s decision to hunger strike in prison in 1920 identified him as a devoted Sinn Feiner standing against British rule.⁵ This type of mortification used the body as a type of text that was meant to be read even beyond the death of the striker, as it allowed them to be immortalized in the martyr tradition despite their death being self-imposed.