“Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still.”- Marker, Devonshire Cemetery

For just about anybody, World War I is synonymous with trench warfare; and for the majority of the war, this was indeed the case. After the brief open warfare stage at the beginning of 1914, and open until the breakthrough of enemy lines in 1918, the war was one of position warfare (1). Yet to assume that in those interceding years of trench warfare there were no advances or developments on the part of those defending the trench lines would be erroneous.

Pre-war French military doctrine, mirrored by the other European powers, favored the offensive. A section of a line could only be placed on the defensive if it were in support of another sector that was on the offensive. Further, the idea of holding a defensive line was entirely static and self-sacrificial. If under attack, it was imperative that the defenders would hold to the very last man (2).

In the early stages of the war, pre-conceived notions of how a defensive engagement should be fought rapidly changed in the face of modern artillery. Strong, above-ground structures were often placed in strategically sound locations, but they were far apart and extremely visible (3). This notion of “strong point” defense was easily exploited in the era of modern artillery. These conspicuous positions could be destroyed by howitzers and field pieces, without being able to offer any counter fire. Further once they were assaulted by enemy infantry the individual strongpoints were often too far apart to offer any assistance to one another. The Germans learned the use need to camouflage their positions rather quickly, yet unfortunately the Allies learned this only slowly (4). Continuous fronts of trenches soon replaced these strong points.

At the beginning of the war, commanders often felt that the fields of view available to their defensive positions were incredibly important. However, this often meant putting men in more exposed areas, and making them easy targets for enemy fire. Thus, by 1915 trenches were often constructed on the reverse side of a slope with observation posts at the crest. This way the defenders could still view the enemy, but their actual defensive positions were at far less risk (5).

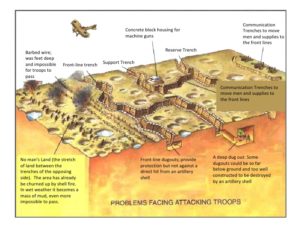

Trench lines themselves were surprisingly complex. Though at the war they were rudimentary at best, advances in organization and depth came quickly. Each trench line consisted of two trenches, a fighting trench and a rearward communication trench roughly 12 meters apart. 50-100 meters behind this first line would be a second trench line similarly constructed, these two would form one position (6). Often a defensive front would consist of multiple positions, for instance the German defensive lines during the Battle of the Somme were made up of three positions with a total depth of 500-1,000 meters. These were further supplemented by a reserve sector 2-4 kilometers behind the advance positions which was made up of one or two trench systems (7).

Within these trenches a number of weapons were found in addition to the standard infantry rifles. Most notable were the machine guns. For a brief time following the Artois Offensive of the Allied powers in late 1915 the Germans actually began placing their machine gun nests out ahead of the main lines. This served to keep them out of artillery fire, as well as surprising the advancing enemy infantry (8). Afterwards it was often found best to keep machine guns within the trench systems, and wherever possible to keep them sheltered with clear lanes of fire (9). Both of these sites were soon found and stymied by enemy artillery fire however. So machine guns were once again moved later in the war to the intermediate zones between trench lines. Here they could camouflage themselves and also offer supporting fire for their own infantry if a trench line were overrun (10).

Lastly, the old idea of holding a trench at all costs was discarded quickly in World War I. By 1915, most advance trench lines were only thinly held, so as to give alarm to the second trench line that an attack was coming. To try and hold the front trench line, well within enemy artillery range simply proved far too costly to be logical. Further by keeping the majority of forces rearward, once an attack started they were freer to move to reinforce positions where increased strength was more necessary (11). To offset this lack of strength in the front line, it was learned that counterattacking and depth of positions were crucial. Counterattacks were often launched almost immediately, and because the enemy was generally occupying positions destroyed by their own artillery they were easier to drive out. Depth of position as aforementioned had benefits of forewarning of attacks to deeper positions but also it put further rearward lines out of enemy artillery range (12).

In general many of the defensive lessons learned from World War I still exist today. Continuous lines of defense have replaced traditional strongpoints in many places; perhaps most notably along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea. Though the connection of World War I with trench warfare is certainly fair, it must be remembered that the concepts involved were ever changing.

- Henri Lucas, Pascal Marie, The Evolution of Tactical Ideals in France and Germany during the War of 1914-1918, 1923, pg. 3.

- Ibid, pgs. 5-8.

- Ibid, pg. 27.

- Ibid, pg. 27.

- Balck, William, Development of Tactics- World War, 1922, pg. 54.

- Ibid, pgs. 54,58.

- Ibid, pg. 72.

- Lucas, Evolution of Tactical Ideals, pg. 53.

- Balck, Development of Tactics, pg. 68.

- Ibid, pg. 153.

- Lucas, Evolution of Tactical Ideals, pg. 47.

- Balck, Development of Tactics, pgs. 79, 152-153