On April 29th 1992, the lid flew off of South Central Los Angeles. The LA riots began in the late afternoon, sprouting from popular discontent with the verdict of a trial of four out of the five LAPD officers who beat Rodney King on March 3rd of the previous year: all were found not-guilty on assault charges, and three of the four were cleared on charges of excessive force. This first manifested itself in public popular discontent, followed by isolated incidents of minor crimes and racially-charged assaults on whites passing through certain sections of South Central which culminated in large crowds of blacks encroaching upon LAPD officers, who promptly fled the scene as they found themselves outnumbered and reluctant to use any modicum of force in light of the fresh verdict and raw, renewed tensions. [1]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKQIeSq4FK4

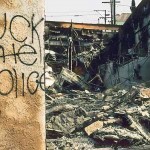

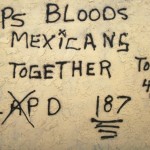

For two straight days, South Central was in state of bacchanalian pandemonium. The looting and burning of businesses, especially of liquor stores and Korean-owned businesses, respectively, was pervasive. [2] Koreans, whose businesses accounted for 34% of all businesses which sustained losses, and 46% of those which were totally burned to the ground, were targeted as they were seen as representative of a white “over-class”. [3] Most of the action and iconographic photography — murders, looting, property damage, and associated arrests resulting in 53 deaths, thousands of injuries and around $1,000,000,000 in property damage — occurred in these first two days. [4][5] The violent and chaotic situation on the ground, and especially the ethnically-driven targeting of buildings for their destruction, echoes The Troubles’ beginnings in 1969 Belfast and Derry.

By Friday, May 1st, 10,000 California National Guard (CANG) troops had been sent into afflicted areas, and that night President George H.W. Bush made a televised address stating that there was an “urgent need to restore order”, and denounced the rioting as “the brutality of a mob, plain and simple”. He continued: “And let me assure you: I will use whatever force is necessary to restore order”. The rest of his address is spent extending his sympathies to King and victims of LAPD abuse, explaining how a new federal trial would be assembled to re-try the officers involved in the King beating, and detailing how elements of the 7th Infantry Division and 1st Marine Division would be sent in to supplement CANG troops to form what will be later referred to as “Joint Task Force Los Angeles”, or “JTF-LA”. [6]

From this point, violence of all sorts rapidly fizzled out. JTF-LA patrolled the streets through to the end of the riots on May 4th. They intervened in violent incidents, and generally acted to support LAPD operations through providing them with additional manpower, the representation of a force more well-respected by the local community, and the introduction of an intermediate “third party” that was governmental in nature but not regarded with the same vitriol as police due to a lack of history of abuse between federal troops and the residents of Los Angeles. [7]

Why did this happen? (Comparison to Northern Ireland)

The main, salient reason that the LA Riots occurred was seriously brutal and, more importantly, indiscriminate tactics used by the LAPD throughout the 1980s. The LAPD pulled over and harassed black youths and men, and, to a lesser degree, hispanic youths and men, far more often than they did whites or asians.[8] This was due in large part to the fact that the LAPD was, historically and contemporaneously, a by-and-large a white police force.[9] This had been recognized as a problem sometime around the time of the adoption of the Blake Consent Decree in 1981, at which point the LAPD was 81% white, and the LAPD had actually made a conscious effort to hire more hispanic, asian, and black officers in an effort to make the force more involved with and representative of the communities within its jurisdiction, but by 1990, 63% of its officers were still white.[10][11] The LAPD’s solution for its problem of being structurally nonrepresentative of its jurisdiction was also severely hampered by other factors. The integration of minority officers at all levels of command was incomplete and desultory, at best, and these officers tended to be vastly underrepresented in managerial positions and other higher echelons of command.[12][13] The fact that LAPD officers of all ethnicities harassed and brutalized minorities also led to special resentment amongst minority communities towards minority officers in a similar fashion to how Catholics had little respect for Catholic RUC constables.[14][15]

As for actual brutalization, there are clear indications that the LAPD had a serious problem with use of excessive force. In a 1990 survey, 16% of officers did not disagree with the statement that they would be unjustified in administering “street justice” (beatings up to and including those capable of breaking bones and rupturing organs) to suspects “with a bad or uncooperative attitude”.[16] What’s troubling is that such a sentiment was so widely pervasive within the department that 16% of officers believed this so strongly that they saw nothing wrong with putting that down on an internal investigation survey administered months after the widely-publicized Rodney King beating. 8,274 complaints were filed against LAPD officers from 1986-1990, and of these, a quarter were for excessive force and 14.5% for “improper tactics”.[17] The amount of incidents where complaints were filed is very high, and it’d be reasonable to assume that many other cases went unreported. Typical of these cases would be the case of Michael Bernal, who was arrested for outstanding traffic warrants. In May 1981, he was beaten by several LAPD officers in his holding cell so badly that he lost two teeth and suffered multiple concussions resulting in permanent brain damage. The officers engaged him in a chokehold, punched and kicked him in the face and groin, and slammed his head into the floor.[18] MDT messages (basically proto-text-messages sent between LAPD squad cars) indicated that such beatings were regularly administered equal parts for fun and to “send a message”.[19] The pervasiveness of these sorts of “street justice” tactics led to a widespread hatred for the LAPD, and was a main reason as to why individuals participated in the 1992 riots. This is similar to how the Troubles only began in earnest once Catholics began joining the PIRA after some of them being beaten senseless for days on end by RUC constables and British Army soldiers during internment.[20]

Lastly, the way in which President Bush addressed the riots and the rioters is in stark contrast to how Margaret Thatcher addressed the Troubles and Catholic/Nationalist violent non-state actors. Bush, while unequivocally criticizing rioters and threatening the use of lethal force to stop them, did not deny there was a policing problem within LA, and in fact, took measures to reconcile them, namely, a federal re-trial of the officers involved in the Rodney King beating which precipitated the 1992 LA riots. Not ten years later, the LAPD was put under federal supervision until it was deemed fixed enough to operate independently.[21] In stark contrast, Thatcher allowed the Northern Irish government which had basically supported discriminatory and brutal policing tactics from its inception to continue doing so, allowed federal (British) troops to partake in said tactics through internment, and dismissed any PIRA or Nationalists by flatly refusing to recognize they acted violently as a result of legitimate gripes with the government, stating “A crime is a crime is a crime”.

With the above analyses, the questions which beg to be asked are:

Morality aside, what pragmatic benefits are there to the use of strongarm police tactics? Are there any at all? How long can the use of such tactics be sustained before there is backlash?

When is it appropriate to take a “strong” stance against non-state agitators? When does leeway or negotiation become tolerable, viable, or even necessary?

Why did the use of federal troops bring an end to the LA Riots, but only exacerbate the troubles?

The main difference between the British Army troops in Northern Ireland during The Troubles and the troops of JTF-LA during the riots, other than the fact that the latter was far more successful at restoring order, was that JTF-LA existed in a sort of “third space” that was neither violent non-state actor or police body with a history of abuse. Is this factor key to the success of federal troops in quelling civil unrest? Can federal soldiers be used to effectively end riots or civil unrest if they compromise their position within said “third space”?

Citations:

[1] http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/1993/05/23/the-untold-story-of-the-la-riot[2] Ibid.

[3] Mark Baldassare, The Los Angeles Riots: Lessons for the Urban Future, p.5; p.152-155

[4] http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~oliver/soc220/Lectures220/AfricanAmericans/LA%20Riot%201992%20Deaths.htm

[5] http://www.npr.org/2012/04/29/151608071/after-l-a-riots-an-effort-to-rebuild-a-broken-city

[6] https://web.archive.org/web/20060216041435/http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/papers/1992/92050105.html

[7] http://fmso.leavenworth.army.mil/documents/rio.htm

[8] http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/1993/05/23/the-untold-story-of-the-la-riot (page 2)

[9] Christopher Commission pages 74-76

[10] Ibid., p.71

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., p.78-82

[13] Ibid., p. 81-83

[14] http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/1993/05/23/the-untold-story-of-the-la-riot (page 2)

[15] Brendan O’Leary, The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland, p. 125-127

[16] Christopher Commission page 34

[17] Christopher Commission table 3-1 (between pages 34/45)

[18] Ibid., page 58

[19] Ibid., page 49-54

[20] John Conroy, Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People, page 46

[21] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/lapd/later/decree.html

Roadmap

3 Replies to “Policing in Northern Ireland: LA, 1992”