In opposition to what Yeats probably would have wanted, I have done a rudimentary word frequency analysis of a few collections of his poetry. The website I used (http://textalyser.net) is one of many text analysis tools. One of the things it does is list the number of times each word is used in a given chunk of text. I tried out five Yeats collections to see if I could notice any trends: The Wind among the Reeds, In the Seven Woods, The Green Helmet, Responsibilities, and The Wild Swans at Coole. I choose these texts partially because they span Yeats’ transition from his early Celtic Twilight phase to his middle phase, but mostly because they were the only ones easily accessible online.

By default, the website filters-out unhelpfully common words like articles and some prepositions/conjunctions. Also, for the purpose of this analysis, I excluded all one-and-two-character words to cut back on pronouns like “I” and “me” because Yeats, ever the egotist, uses them so often that they overshadow other words. It should be assumed that the self is a common enough subject of interest in poetry that it does not deserve an extensive in-depth analysis. What results is a list of the most common significant words in Yeats’ various collections of poetry. As it turns out, interesting trends in Yeats’ word preferences can be traced from collection to collection, and many of these trends, once graphed, coincide with the poet’s transformation over time.

It may be useful to page through the attached Excel workbook. The first sheet displays the graphs that I have posted below and the second sheet contains my raw data. The data is helpful in that it lists the thirty most frequently-used words in each of the five collections. Below are the interpretations of my results. (You may have to click on the graphs to get a clearer view.)

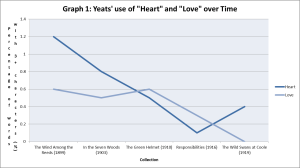

Graph 1: Yeats’ use of “heart” and “love” over time.

This graph plots the number of times Yeats uses the words “heart” and “love” in his poetry. I selected these two words in particular because their plot coincides with the poet’s transition from his dreamy Celtic Twilight poetry and later, more realistic works. For the most part, one can observe a gradual decline in the use of both words. This trend is indicative of Yeats’ transition from romanticism toward realism. For example, the word “heart” constitutes 1.2% of all significant words in The Wind among the Reeds while Responsibilities, a much later work, only uses the word .1% of the time. A similar trend can be observed for the word “love,” which gradually declines in use from 0.6% in The Wind among the Reeds to being statistically non-existent by The Wild Swans at Coole.

Although this is not exactly visible in the graph, many of the top thirty words (see Excel sheet) deal with physical human characteristics. The words “hair,” “pale,” and “eyes” are used 19, 15, and 15 times, respectively. All these words make the top ten list, outweighing the more abstract words commonly associated with beauty (“dream” (12), “stars” (10), “rose” (10), and “fire” (9)). Yeats’ focus on the physical aspects of beauty, especially hair, points toward his early infatuation with the Pre-Raphaelites. As it turns out, the use of these physical, yet unrealistic words declines from collection to collection, which again coincides with the poet’s eventual delineation from romanticism.

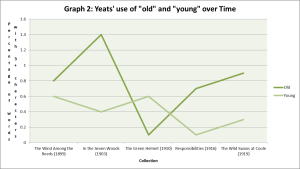

Graph 2: Yeats’ use of “old” and “young” over time.

In this graph, one can see an interesting fluctuation in Yeats’ use of the words “young” and “old.” Although the topic of age and death permeate all of his writings, it is clear that he places less emphasis on them in The Green Helmet, which marks Yeats’ middle phase. Perhaps this is because, in The Green Helmet, he begins talking about real people rather than idealized mythical characters. Also, his ponderings on love are less abstract in his middle phase poems. This is backed up by the fact that this collection contains Yeats’ concept of “The Mask.” It is as if Yeats, in an effort to contradict his previous lamentations on the advance of old age, he focuses instead on youth. After this collection, however, it seems that political turmoil turns him back on track for Responsibilities and The Wild Swans at Coole.

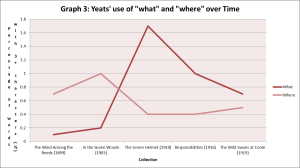

Graph 3: Yeats’ use of “what” and “where” over time.

This is perhaps the most interesting graph when it comes to analyzing Yeats’ transitive phase. Looking at the words alone, it is easy to see that, as time progresses, the poet starts using “where” less often and “what” more often. In his early writings, Yeats focused almost exclusively on Irish themes and geographical locations. As a result, the poems from this era are more likely to contain the word “where.” Location is critically important at this time in his life; the evidence shows that “where” is most important in the collections The Wind among the Reeds and In the Seven Woods. From The Green Helmet and onward, its use generally stays low. This trend lends to the idea that Yeats, as he transformed as a poet, focused less on locations and more on (real) individuals and ideas. In later collections, “what” effectively replaces “where.” This shift is important because it shows that Yeats seems to be asking more questions about life than merely filling it with embellished characters and symbolic locations. The poems in The Wild Swans at Coole are no doubt more real than, say, the Fergus poems.

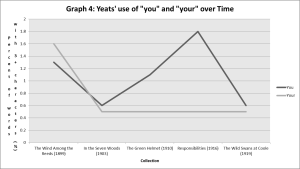

Graph 4: Yeats’ use of “you” and “your” over time.

One can observe a precipitous decline in the use of both words from The Wind among the Reeds and In the Seven Woods. This, I believe, also has something to do with Yeats’ partial demystification of Maud Gonne after her rejection of his second and third marriage proposals. Just as his focus drifts away from Pre-Raphaelite symbolism, Yeats slowly steps away from focusing on an idealized subject. What is interesting, however, is the sudden spike in the use of “You” in The Green Helmet and Responsibilities. This may be due to the reflective nature of these collections. In Responsibilities, for example, Yeats spends a lot of time thinking about his role in society and how his ancestors have contributed to his (perceived) sense of nobility. Thus, the “you”s tend to be more accusative descriptive than dreamy and abstract.

Overall, the frequency with which Yeats uses his words is transitive enough to discern several interesting trends from collection to collection. Please take a look at the attached Excel sheet if you are interested in looking at other correlations and differences in his word choice.