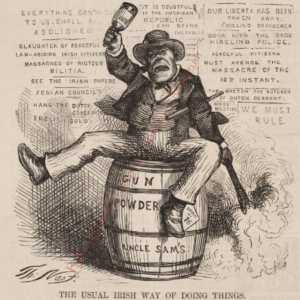

Yeats uses Celticism to counter these negative stereotypes such as those portrayed in the Punch cartoons. To understand Yeats’ complicated perspectives, it is helpful to know of his background: he is Irish but spent most of his early life in London. He is Protestant but not an imperialist; however, he supports Anglo-Irish leadership and the nationalists’ revolutionary efforts. Yeats’ views directly impact his complex perspective when it comes to his writing.

Similar to how Yeats’ attitudes contradict each other, his methods of portraying an ideal Irish identity are also complicated. Sometimes, being Irish is all about being tied to the unique landscape. Other times, he works toward formulating a more universal Celtic spirit that ultimately determines the ideal Irishness. These ideas negate each other — as soon as one is established, Yeats shuttles to the other one, creating an unstable tone. Despite Yeats’ efforts, there really is no true ideal.

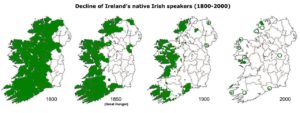

The Celtic Twilight is one of Yeats’ earliest collections of works that aims to answer his question, “Can we not build up a national tradition, a national literature, which shall be nonetheless Irish in spirit from being English in language?” This discussion of ‘national’ ideas emphasizes the dismantling of stereotypes and pursuit of an ideal Irish identity.

An example of this negation between the two different ideas is evident in “A Voice.” In this work, Yeats begins by describing walking on “marshy ground” — a reference to the bogs of Ireland — before quickly moving into telling of being “preoccupied with Aengus and Edain, and with Manannan, God of the Sea”. This discussion of Irish folklore represents the Celtic spirit, yet it cancels out the landscape portion. In his attempt to disassemble the derogatory Irish stereotypes, Yeats tries to have these separate ideals both ways, which is unattainable.

Yeats:

Yeats uses Celticism to counter these negative stereotypes such as those portrayed in the Punch cartoons. To understand Yeats’ complicated perspectives, it is helpful to know of his background: he is Irish but spent most of his early life in London. He is Protestant but not an imperialist; however, he supports Anglo-Irish leadership and the nationalists’ revolutionary efforts. Yeats’ views directly impact his complex perspective when it comes to his writing.

Similar to how Yeats’ attitudes contradict each other, his methods of portraying an ideal Irish identity are also complicated. Sometimes, being Irish is all about being tied to the unique landscape. Other times, he works toward formulating a more universal Celtic spirit that ultimately determines the ideal Irishness. These ideas negate each other — as soon as one is established, Yeats shuttles to the other one, creating an unstable tone. Despite Yeats’ efforts, there really is no true ideal.

The Celtic Twilight is one of Yeats’ earliest collections of works that aims to answer his question, “Can we not build up a national tradition, a national literature, which shall be nonetheless Irish in spirit from being English in language?” This discussion of ‘national’ ideas emphasizes the dismantling of stereotypes and pursuit of an ideal Irish identity.

An example of this negation between the two different ideas is evident in “A Voice.” In this work, Yeats begins by describing walking on “marshy ground” — a reference to the bogs of Ireland — before quickly moving into telling of being “preoccupied with Aengus and Edain, and with Manannan, God of the Sea”. This discussion of Irish folklore represents the Celtic spirit, yet it cancels out the landscape portion. In his attempt to disassemble derogatory Irish stereotypes, Yeats tries to have these separate ideals both ways, which is unattainable.

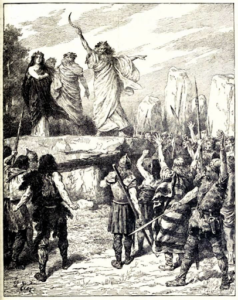

The Celtic Ideal: The Warrior and the Druid

The ancient Celts, the origin of much of Ireland’s mythology and folklore, were warrior people. The Celts idealized courage, wisdom, eloquence and cunning in their warriors and emphasized the importance of an “agrarian society that venerates nature.” These beliefs have survived through the myths and folklore that permeate Irish culture. In his article, “The Prisoners of the Gods” (1898), Yeats said, “the peasants believe in their ancient gods and that to them, as to their forbears, everything is inhabited and mysterious. The gods gather in raths or forts, and about the twisted thorn trees, and appear in many shapes, now little and grotesque, now tall, fairhaired and noble, and seem busy and real in the world, like the people in the markets or at the crossroads.” Even as modernity encroached on Ireland, its people held onto that magic passed onto them for centuries.

From an outside perspective, especially that of the English who sought to conquer these people, the Irish likely seemed superstitious and strange. Long after most nations had moved onto prayer and sermons, the Irish still spoke as if the gods walked among them and faeries lived in the hills. Alongside their general scorn for materialism and urbanization, these “pagan” beliefs would have set the Irish apart from the English in a way that was not easily reconciled. When stereotypes of Irish barbarism, and uncivilized pagan customs emerged, the English likely felt somewhat justified while the Irish recognized such labels as an attack on their culture and national identity.

When Revivalists, such as Yeats, and nationalist politicians, such as De Valera, proposed the Irish ideal as a return to the country-side, a rejection of materialism, and an embracement of tradition and the family, they reintroduced timeless Celtic ideals to the Irish public. Rather than accepting criticism of their culture, the Irish held fast to their cultural identity and sought to replace derogatory stereotypes with the image of Ireland as it once was. The problem with this approach is that while is succeeded in some part by reinvigorating Irish culture, it was also unrealistic. Progress required modernization, and while Ireland continued to urbanize and progress as a country, the Irish people were also being encouraged to embrace tradition and the simple, country life. For many people struggling to survive in cities, such as Dublin, the Irish ideal was impossible to meet.

Click here to return to front page.