Sandbox Post –

This is a temporary place where we’ll show you how to add various types of information to the website.

Formatting:

- Italics, Bold, Underline

- Indenting

- Changing text color

- Bulleted lists

Inserting a link:

To a site on the course website

To another website

Hyperlinking

Inserting media

Inline media (for example a video)

Publishing your post

Linking to your post

Sample Textual Analysis: Coursepack on Plantations and Penal Laws

Violence in Early Modern English Writings on Ireland

[Note: This is a sample annotation, showing one possibility for your web version of the analytical paper. This isn’t the only way you can put together your annotation, but it’s one example of what is possible. This also runs a bit longer than what we’re expecting from your work.]In John Derricke’s Image of Ireland (1581), the author asserts that the 16th century population of Ireland engaged in indiscriminate acts of violence, delighting in destruction for the sake of destruction. In the second woodcut in the text, for example, Derricke’s caption reads:

They spoil, and burn, and bear away, as fit occasions serve,

They spoil, and burn, and bear away, as fit occasions serve,

And think the greater ill they do, the greater praise deserve:

They pass not for the poor man’s cry, nor yet respect his tears,

But rather joy to see the fire, to flash about his ears.

To see both flame, and smoldering smoke, to dark the crystal skies,

Next to their prey, therein I say, their second glory lies. [1]

Edmund Spenser echoed the point in the View of the Present State of Ireland (1596). In a passage that was not included in the excerpts we read for class, Irenaeus (speaking for Spenser) asserted that Ireland:

…is a nation ever acquainted with wars, though but amongst themselves, and in their own kind of military discipline, trained up from their youths: which they have never yet been taught to lay aside, nor made to learn obedience unto the law, scarcely to know the name of law… [2]

In both passages, indiscriminate violence is presented as something integral to Irish culture. The above quote from Spenser makes this explicit, asserting that civil customs, discipline, and obedience must be taught at an early age. The civility of the Irish, both suggest, can be judged by their willingness to subordinate themselves before the dual authority of the English crown and English laws. Thus, Derricke concludes, the mark of the Great O’Neill’s loyalty could be found in his oath to Elizabeth, “to maintain the sacred right, of such a Virgin Queen”. [1]

Both Derricke and Spenser assert that indiscriminate violence carried out by the Irish must be met with violence carried out by English soldiers. Because the rebellious Irish operated outside the boundaries of law, they suggest, English soldiers could carry out acts that might otherwise seem excessively brutal or in violation of early modern codes of warfare. Derricke thus expresses delight in the dismembering of Irish rebels in the field: “To see a soldier toze a kern, O Lord it is a wonder/And eke what care he taketh to part, the head from neck a sunder”. Spenser strikes out in a slightly different direction, suggesting that direct violence against Irish rebels might not be necessary. Instead, in one of the most famous passages from the View, he imagines the successful conclusion of a scorched earth strategy that would have the effect of starving out the recalcitrant population. Recalling similar strategies used by English soldiers during the Desmond Rebellions, Irenaeus describes the endgame of this approach:

Out of every corner of the wood and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked anatomies [of] death, they spoke like ghosts, crying out of their graves; they did eat of the carrions, happy where they could find them, yea, and one another soon after, in so much as the very carcasses they spared not to scrape out of their graves. And if they found a plot of water-cresses or shamrocks, there they flocked as to a feast for the time, yet not able long to continue therewithal; that in a short space there were none almost left, and a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast. [1]

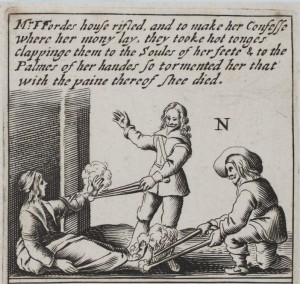

Looking ahead almost a half century to the 1641 Rising, similar themes can be discerned in English writing on the conflict. The images below, sampled from James Cranford’s The Tears of Ireland, a 1642 work published in Ireland, presents horrific scenes of violence carried out by Irish rebels against English settlers [3]:

It should be noted that much of this violence was exaggerated in the London press, which tended to publish sensationalized accounts and reflected England’s political context in the early 1640s, particularly the emerging conflict between Charles I and the Long Parliament. Recent scholarship, which draws heavily on the 1641 Depositions at Trinity College Dublin, assess the ways that these assertions were exaggerated and demonstrates some of the more complicated motives for the violence that did occur in 1641 [4].

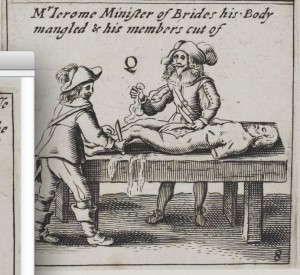

The presentation of the relationship between Roman Catholicism and violence is an important difference between the late 16th century writings of Derricke and Spenser and the accounts of the 1641 Rising. Derricke and Spenser had little to say about Irish religion. For example, Derricke’s “Friar Smellfeast” (“Who plays in Romish toys the ape, by counterfeiting Paul”) can be seen as a generically gluttonous and duplicitous figure, but hardly harmful [1]. By contrast, in the image below, Cranford presents the Irish rebels of 1641 as inherently anti-religious in specifically attacking and dismembering Protestant ministers.

The next image from Cranford identifies the source of this brutality. Cranford does not present violence as a symptom of disorder and incivility, but rather as something encouraged by active involvement of Roman Catholic clergy who “anoint the rebels with their sacrament of unction before they go to murder and rob, assuring them that for their meritorious service if they be killed [they] shall escape Purgatory and go to Heaven immediately”.

This view of the 1641 Rising extends into contemporary times. In the 1970s and 1980s, Ian Paisley invoked the 1641 Rising in his polemical speeches on the Troubles, comparing the Provisional IRA to the rebels of 1641 [5]. Likewise, during the tense standoffs surrounding Orange Order routes in the late 1990s, marchers carried banners depicting the alleged drowning of Protestants at Portadown in 1641 [6] and the ianpaisley.org website, which is affiliated with the European Institute of Protestant Studies, includes an essay by Dr. Clive Gillis, entitled “The Irish Rebellion of 1641: A Vicious, Unprovoked Bloodbath Engineered by Rome against Protestants” [7].

One of the important themes that we discussed throughout our class was historical memory and how community identities often reference stories of past events as part of a collective and usable past. This material from 1641 seems important to our discussions of Northern Ireland and Unionist commemoration. King Billy obviously takes center stage in Unionist iconography and collective memory – we saw the triumphant arches in several towns and the King William mural in the Fountain neighborhood of Derry – but 1641 seems equally important. William of Orange is a symbol of Protestant victory and suppression of Roman Catholicism. This suppression only makes sense if Catholics were perceived as a threat. The 1641 Rising provided accounts of extreme violence targeting Protestants and encouraged by the Roman Catholic Church. Understanding that view of the Rising, although it is badly distorted and problematic, does help make sense of some of the anxieties expressed by Unionist elements over the years.

References

[1] July 18 Coursepack on Plantation and Penal Laws (https://irishstudies.sunygeneseoenglish.org/july-18-coursepack-on-plantation-and-penal-laws/) [2] Renascence Edition of Edmund Spenser, View of the Present State of Ireland (http://pages.uoregon.edu/rbear/veue1.html) [3] Irish Comics Wiki: The Teares of Ireland (http://irishcomics.wikia.com/wiki/Teares_of_Ireland) [4] Examples can be found in Raymond Gillespie, “The Murder of Arthur Champion and the 1641 Rising in Fermanagh”, Clogher Record 14 (1993), pp. 52-66 and Hilary Simms, “Violence in County Armahg”, in Brian Mac Cuarta (ed.), Ulster 1641: Aspects of the Rising (Belfast: 1997), pp. 123-138. [5] R. Davis, “The Manufacturing of Propagandist History by Northern Ireland Loyalists and Republicans”, in Yonah Alexander and Alan O’Day (eds.), Ireland’s Terrorist Dillema (Dordrecht: 1986), p. 166. [6] Susan McKay, Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People (Belfast: 2000), p. 143. [7] Clive Gillis, “Days of Deliverance, Part 7: The Irish Rebellion of 1641: A Vicious, Unprovoked Bloodbath Engineered by Rome against Protestants” (http://www.ianpaisley.org/article.asp?ArtKey=deliverance7)1937 Constitution of Ireland (with Amendments)

THE CONSTITUTION OF IRELAND (BUNREACHT NA hÉIREANN)

Enacted 1937

(Excerpts)

Sections deleted by constitutional amendment are noted in red. Sections added by amendment are noted in blue.

PREAMBLE

In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred, We, the people of Éire, Humbly acknowledging all our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial, Gratefully remembering their heroic and unremitting struggle to regain the rightful independence of our Nation, And seeking to promote the common good, with due observance of Prudence, Justice and Charity, so that the dignity and freedom of the individual may be assured, true social order attained, the unity of our country restored, and concord established with other nations, Do hereby adopt, enact, and give to ourselves this Constitution.

Article 2

The national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas.

[Deleted by 19th amendment, 1998 (part of the Good Friday Agreement)]

Article 3

Pending the re-integration of the national territory, and without prejudice to the right of the Parliament and Government established by this Constitution to exercise jurisdiction over the whole of that territory, the laws enacted by that Parliament shall have the like area and extent of application as the laws of Saorstát Éireann and the like extra-territorial effect.

[Deleted by 19th amendment, 1998 (part of the Good Friday Agreement)]

Article 40: Personal Rights

Section 3:

Clause 1: The State guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate the personal rights of the citizen.

Clause 2: The State shall, in particular, by its laws protect as best it may from unjust attack and, in the case of injustice done, vindicate the life, person, good name, and property rights of every citizen.

Clause 3: The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.

[Clause added by 8th amendment, 1983]

This subsection shall not limit freedom to travel between the State and another state.

[Sub-clause added by 13th amendment, 1992]

This subsection shall not limit freedom to obtain or make available, in the State, subject to such conditions as may be laid down by law, information relating to services lawfully available in another state.

[Sub-clause added by 14th amendment, 1992]

Section 6: The State guarantees liberty for the exercise of the following rights, subject to public order and morality:

Clause 1: The right of the citizens to express freely their convictions and opinions. The education of public opinion being, however, a matter of such grave import to the common good, the State shall endeavor to ensure that organs of public opinion, such as the radio, the press, the cinema, while preserving their rightful liberty of expression, including criticism of Government policy, shall not be used to undermine public order or morality or the authority of the State. The publication or utterance of blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter is an offense which shall be punishable in accordance with law.

Article 41: The Family

Section 1

Clause 1: The State recognizes the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society, and as a moral institution possessing inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law.

Clause 2: The State, therefore, guarantees to protect the Family in its constitution and authority, as the necessary basis of social order and as indispensable to the welfare of the Nation and the State.

Section 2

Clause 1: In particular, the State recognizes that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.

Clause 2: The State shall, therefore, endeavor to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

Section 3

Clause 1: The State pledges itself to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, on which the Family is founded, and to protect it against attack.

Clause 2: No law shall be enacted providing for the grant of a dissolution of marriage.

[Deleted by 15th Amendment, 1996]

Clause 2: A Court designated by law may grant a dissolution of marriage where, but only where, it is satisfied that—

- at the date of the institution of the proceedings, the spouses have lived apart from one another for a period of, or periods amounting to, at least four years during the previous five years,

- there is no reasonable prospect of a reconciliation between the spouses,

- such provision as the Court considers proper having regard to the circumstances exists or will be made for the spouses, any children of either or both of them and any other person prescribed by law, and

- any further conditions prescribed by law are complied with. [Added by 15th Amendment, 1996]

Clause 3: No person whose marriage has been dissolved under the civil law of any other State but is a subsisting valid marriage under the law for the time being in force within the jurisdiction of the Government and Parliament established by this Constitution shall be capable of contracting a valid marriage within that jurisdiction during the lifetime of the other party to the marriage so dissolved. [Deleted by 15th Amendment, 1996]

Clause 4: Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex [Added by 34th Amendment, 2015]

Article 42: Education

Section 1

The State acknowledges that the primary and natural educator of the child is the Family and guarantees to respect the inalienable right and duty of parents to provide, according to their means, for the religious and moral, intellectual, physical and social education of their children.

Clause 1: Parents shall be free to provide this education in their homes or in private schools or in schools recognised or established by the State.

Clause 2:

- The State shall not oblige parents in violation of their conscience and lawful preference to send their children to schools established by the State, or to any particular type of school designated by the State.

- The State shall, however, as guardian of the common good, require in view of actual conditions that the children receive a certain minimum education, moral, intellectual and social.

Clause 3: The State shall provide for free primary education and shall endeavor to supplement and give reasonable aid to private and corporate educational initiative, and, when the public good requires it, provide other educational facilities or institutions with due regard, however, for the rights of parents, especially in the matter of religious and moral formation.

Clause 4: In exceptional cases, where the parents for physical or moral reasons fail in their duty towards their children, the State as guardian of the common good, by appropriate means shall endeavor to supply the place of the parents, but always with due regard for the natural and imprescriptible rights of the child.

Article 44: Religion

Section 1

Clause 1: The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion.

Clause 2: The State recognizes the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the citizens.

[Deleted by 5th Amendment, 1973]

Clause 3: The State also recognizes the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations and the other religious denominations existing in Ireland at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution.

[Deleted by 5th Amendment, 1973]

Section 2

Clause 1: Freedom of conscience and the free profession and practice of religion are, subject to public order and morality, guaranteed to every citizen.

Clause 2: The State guarantees not to endow any religion.

Clause 3: The State shall not impose any disabilities or make any discrimination on the ground of religious profession, belief or status.

Article 45: Directive Principles of Social Policy

Section 4

Clause 2: The State shall endeavor to ensure that the strength and health of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children shall not be abused and that citizens shall not be forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their sex, age or strength.

Full text of 1937 Constitution (with subsequent amendments) available at: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Ireland_(consolidated_text)

Coursepack on the Anglo-Irish Treaty

THE TREATY

Excerpts from the Anglo-Irish Treaty (6 December 1921)

Full text at http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/politics/docs/ait1921.htm

1. Ireland shall have the same constitutional status in the Community of Nations known as the British Empire as the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand and the Union of South Africa, with a Parliament having powers to make laws for the peace, order and good government of Ireland and an Executive responsible to that Parliament, and shall be styled and known as the Irish Free State.

3. The representative of the Crown in Ireland shall be appointed in like manner as the Governor-General of. Canada and in accordance with the practice observed in the making of such appointments.

4. The oath to be taken by Members of the Parliament of the Irish Free State shall be in the following form:

I ………………. do solemnly swear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State as by law established and that I will be faithful to H.M. King George V, his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of the group of nations forming the British Commonwealth of Nations.

7. The Government of the Irish Free State shall afford to His Majesty’s Imperial Forces:

(a) In time of peace such harbour and other facilities as are indicated in the Annex hereto, or such other facilities as may from time to time be agreed between the British Government and the Government of the Irish Free State; and

(b) In time of war or of strained relations with a Foreign Power such harbour and other facilities as the British Government may require for the purposes of such defence as aforesaid.

8. With a view to securing the observance of the principle of international limitation of armaments, if the Government of the Irish Free State establishes and maintains a military defence force, the establishments thereof shall not exceed in size such proportion of the military establishments maintained in Great Britain as that which the population of Ireland bears to the population of Great Britain.

11. Until the expiration of one month from the passing of the Act of Parliament for the ratification of this instrument, the powers of the Parliament and the Government of the Irish Free State shall not be exercisable as respects Northern Ireland and the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, shall so far as they relate to Northern Ireland remain of full force and effect, and no election shall be held for the return of members to serve in the Parliament of the Irish Free State for constituencies in Northern Ireland, unless a resolution is passed by both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in favour of the holding of such election before the end of the said month.

16. Neither the Parliament of the Irish Free State nor the Parliament of Northern Ireland shall make any law so as either directly or indirectly to endow any religion or. prohibit or restrict the free exercise thereof or give any preference or impose any disability on account of religious belief or religious status or affect prejudicially the right of any child to attend a school receiving public money without attending religious instruction at the school or make any discrimination as respects state aid between schools under the management of different religious denominations or divert from any religious denomination. or any educational institution any of its property except for public utility purposes and on payment of compensation.

On behalf of the British Delegation.

D. LLOYD GEORGE.

AUSTEN CHAMBERLAIN.

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL.

L. WORTHINGTON-EVANS.

HAMAR GREENWOOD.

GORDON HEWART.

On behalf of the Irish Delegation.

ART Ó GRÍOBHTHA (ARTHUR GRIFFITH).

MICHEAL Ó COILÉAIN.

RIOBÁRD BARTÚN.

EUDHMONN S. Ó DÚGÁIN.

SEÓRSA GHABHÁIN UÍ DHUBHTHAIGH.

AGAINST THE TREATY

Excerpts from Eamon de Valera, Speech against the Treaty in the Dáil Éireann (19 December, 1921)

Full debate at: http://historical-debates.oireachtas.ie/D/DT/D.T.192112190002.html

I think it would scarcely be in accordance with Standing Orders of the Dçil if I were to move directly the rejection of this Treaty. I daresay, however, it will be sufficient that I should appeal to this House not to approve of the Treaty. We were elected by the Irish people, and did the Irish people think we were liars when we said that we meant to uphold the Republic, which was ratified by the vote of the people three years ago, and was further ratified – expressly ratified – by the vote of the people at the elections last May? When the proposal for negotiation came from the British Government asking that we should try by negotiation to reconcile Irish national aspirations with the association of nations forming the British Empire, there was no one here as strong as I was to make sure that every human attempt should be made to find whether such reconciliation was possible. I am against this Treaty because it does not reconcile Irish national aspirations with association with the British Government. I am against this Treaty, not because I am a man of war, but a man of peace. I am against this Treaty because it will not end the centuries of conflict between the two nations of Great Britain and Ireland.

We went out to effect such a reconciliation and we have brought back a thing which will not even reconcile our own people much less reconcile Britain and Ireland.

If there was to be reconciliation, it is obvious that the party in Ireland which typifies national aspirations for centuries should be satisfied, and the test of every agreement would be the test of whether the people were satisfied or not. A war-weary people will take things which are not in accordance with their aspirations….

I wanted, and the Cabinet wanted, to get a document we could stand by, a document that could enable Irishmen to meet Englishmen and shake hands with them as fellow-citizens of the world. That document makes British authority our masters in Ireland. It was said that they had only an oath to the British King in virtue of common citizenship, but you have an oath to the Irish Constitution, and that Constitution will be a Constitution which will have the King of Great Britain as head of Ireland. You will swear allegiance to that Constitution and to that King; and if the representatives of the Republic should ask the people of Ireland to do that which is inconsistent with the Republic, I say they are subverting the Republic. It would be a surrender which was never heard of in Ireland since the days of Henry II.; and are we in this generation, which has made Irishmen famous throughout the world, to sign our names to the most ignoble document that could be signed.

When I was in prison in solitary confinement our warders told us that we could go from our cells into the hall, which was about fifty feet by forty. We did go out from the cells to the hall, but we did not give our word to the British jailer that he had the right to detain us in prison because we got that privilege. Again on another occasion we were told that we could get out to a garden party, where we could see the flowers and the hills, but we did not for the privilege of going out to garden parties sign a document handing over our souls and bodies to the jailers. Rather than sign a document which would give Britain authority in Ireland they should be ready to go into slavery until the Almighty had blotted out their tyrants. If the British Government passed a Home Rule Act or something of that kind I would not have said to the Irish people, “Do not take it”. I would have said, “Very well; this is a case of the jailer leading you from the cell to the hall,” but by getting that we did not sign away our right to whatever form of government we pleased. I regard myself here to maintain the independence of Ireland and to do the best for the Irish people, and it is to do the best for the Irish people that I ask you not to approve but to reject this Treaty.

You will be asked in the best interests of Ireland, if you pretend to the world that this will lay the foundation of a lasting peace, and you know perfectly well that even if Mr. Griffith and Mr. Collins set up a Provisional Government in Dublin Castle, until the Irish people would have voted upon it the Government would be looked upon as a usurpation equally with Dublin Castle in the past. We know perfectly well there is nobody here who has expressed more strongly dissent from any attacks of any kind upon the delegates that went to London than I did.

The Irish people would not want me to save them materially at the expense of their national honor. I say it is quite within the competence of the Irish people if they wished to enter into an association with other peoples, to enter into the British Empire; it is within their competence if they want to choose the British monarch as their King, but does this assembly think the Irish people have changed so much within the past year or two that they now want to get into the British Empire after seven centuries of fighting? Have they so changed that they now want to choose the person of the British monarch, whose forces they have been fighting against, and who have been associated with all the barbarities of the past couple of years; have they changed so much that they want to choose the King as their monarch? It is not King George as a monarch they choose: it is Lloyd George, because it is not the personal monarch they are choosing, it is British power and authority as sovereign authority in this country.

I hold, and I don’t mind my words being on record, that the chief executive authority in Ireland is the British Monarch╤the British authority. It is in virtue of that authority the Irish Ministers will function. It is to the Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Army, who will be the English Monarch, they will swear allegiance, these soldiers of Ireland. It is on these grounds as being inconsistent with our position, and with the whole national tradition for 750 years, that it cannot bring peace. Do you think that because you sign documents like this you can change the current of tradition? You cannot. Some of you are relying on that “cannot” to sign this Treaty. But don’t put a barrier in the way of future generations.

Parnell was asked to do something like this -to say it was a final settlement. But he said, “No man has a right to set.” No man “can” is a different thing. “No man has a right” – take the context and you know the meaning. Parnell said practically, “You have no right to ask me, because I have no right to say that any man can set boundaries to the march of a nation.” As far as you can, if you take this you are presuming to set bounds to the onward march of a nation.

IN FAVOR OF THE TREATY

Excerpts from Michael Collins, The Path to Freedom (1922)

Full text at http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/on-line-books/the-path-to-freedom-index/

After a national struggle sustained through many centuries, we have today in Ireland a native Government deriving its authority solely from the Irish people, and acknowledged by England and the other nations of the world. Through those centuries – through hopes and through disappointments – the Irish people have struggled to get rid of a foreign Power which was preventing them from exercising their simple right to live and to govern themselves as they pleased, which tried to destroy our nationality, our institutions, which tried to abolish our customs and blot out our civilization, all that made us Irish, all that united us as a nation. But Irish nationality survived. It did not perish when native government was destroyed, and a foreign military despotism was set up. And for this reason, that it was not made by the old native government and it could not be destroyed by the foreign usurping government. It was the national spirit which created the old native government, and not the native government which created the national spirit. And nothing that the foreign government could do could destroy the national spirit. But though it survived, the soul of the nation drooped and weakened. Without the protection of a native government we were exposed to the poison of foreign ways. The national character was infected and the life of the nation was endangered. We had armed risings and political agitation. We were not strong enough to put out the foreign Power until the national consciousness was fully re- awakened. This was why the Gaelic Movement and Sinn FÄin were necessary for our last successful effort.

Success came with the inspiration which the new national movement gave to our military and political effort. The Gaelic spirit working through the Dáil and the Army was irresistible. In this light we must look at the present situation. The new spirit of self-reliance and our splendid unity, and an international situation which we were able to use to our advantage, enabled our generation to make the greatest and most successful national effort in our history. The right of Ireland as a nation under arms to decide its own destiny was acknowledged.

We were invited to a Peace Conference. With the authority of Ireland’s elected representatives negotiations were entered into between the two belligerent nations in order to find a basis of peace. During the war we had gathered strength by the justice of our cause, and by the way in which we had carried on the struggle. We had organised our own government, and had made the most of our military resources. The united nation showed not only endurance and courage but a humanity which was in marked contrast with the conduct of the enemy. All this gave us a moral strength in the negotiations of which we took full advantage. But in any sane view our military resources were terribly slender in the face of those of the British Empire which had just emerged victorious from the world war. It was obvious what would have been involved in a renewal of armed conflict on a scale which we had never met before. And it was obvious what we should have lost in strength if the support of the world which had hitherto been on our side had been alienated, if Ireland had rejected terms which most nations would have regarded as terms we could honourably accept. We had not an easy task.

We have to face realities. There is no British Government any longer in Ireland. It is gone. It is no longer the enemy. We have now a native government, constitutionally elected, and it is the duty of every Irish man and woman to obey it. Anyone who fails to obey it is an enemy of the people and must expect to be treated as such. We have to learn that attitudes and actions which were justifiable when directed against an alien administration, holding its position by force, are wholly unjustifiable against a native government which exists only to carry out the people’s will, and which can be changed the moment it ceases to do so. We have to learn that freedom imposes responsibilities. This parliament is now the controlling body. With the unification of the administration it will be clothed with full authority. Through the parliament the people have the right, and the power, to get the constitution, the legislation, and the economic and educational arrangements they desire. The courts of law, which are now our own courts, will be reorganised to make them national in character, and the people will be able to go to them with confidence of receiving justice. That being so, the Government believes it will have the whole force of public opinion behind it in dealing sternly with all unlawful acts of every kind, no matter under what name of political or patriotic, or any other policy that may be carried out.

The National Army, and the new Irish Police Force, acting in obedience to the Administration, will defend the freedom and rights of the Nation, and will put down crime of whatever nature, sectarian, agrarian or confiscatory. In the special circumstances I have had to stress the Government╒s determination to establish the foundations of the state, to preserve the very life of the Nation. But a policy of development is engaging the attention of all departments, and will shortly be made known. We have a difficult task before us. We have taken over an alien and cumbersome administration.

We have to begin the upbuilding of the nation with foreign tools. But before we can scrap them we must first forge fresh Gaelic ones to take their place, and must temper their steel. But if we will all work together in a mutually helpful spirit, recognising that we all seek the same end, the good of Ireland, the difficulties will disappear. The Irish Nation is the whole people, of every class, creed, and outlook. We recognise no distinction. It will be our aim to weld all our people nationally together who have hitherto been divided in political and social and economic outlook. Labour will be free to take its rightful place as an element in the life of the nation.

In Ireland more than in any other country lies the hope of the rational adjustment of the rights and interests of all sections, and the new government starts with the resolve that Irish Labour shall be free to play the part which belongs to it in helping to shape our industrial and commercial future. The freedom, strength, and greatness of the nation will be measured by the independence, economic well-being, physical strength and intellectual greatness of the people. A new page of Irish history is beginning. We have a rich and fertile country – a sturdy and intelligent people. With peace, security and union, no one can foresee the limits of greatness and well-being to which our country may not aspire. But it is not only within our country that we have a new outlook. Ireland has now a recognised international status. Not only as an equal nation in association with the British nations, but as a member of the wider group forming the League of Nations. As a member of these groups, Ireland’s representatives will have a voice in international affairs, and will use that voice to promote harmony and peaceful intercourse among all friendly nations. In this way Ireland will be able to play a part in the new world movement, and to play that part in accordance with the old Irish tradition of an independent distinctive Irish nation, at harmony, and in close trading, cultural, and social relations, with all other friendly nations. In this sense our outlook is new. But our national aim remains the same – a free, united Irish nation and united Irish race all over the world, bent on achieving the common aim of Ireland’s prosperity and good name.

Underlying the change of outlook there is this continuity of outlook. For 700 years the united effort has been to get the English out of Ireland. For this end, peaceful internal development had to be left neglected, and the various interests which would have had distinct aims had to sink all diversity and unite in the effort of resistance, and the ejection of the English power. This particular united effort is now at an end. But it is to be followed by a new united effort for the actual achievement of the common goal. The negative work of expelling the English power is done. The positive work of building a Gaelic Ireland in the vacuum left has now to be undertaken. This requires not merely unity, but diversity in unity.

When I supported the approval of the Treaty at the meeting of Dáil Éireann I said it gave us freedom – not the ultimate freedom which all nations hope for and struggle for, but freedom to achieve that end. And I was, and am now, fully alive to the implications of that statement. Under the Treaty Ireland is about to become a fully constituted nation.

The whole of Ireland, as one nation, is to compose the Irish Free State, whose parliament will have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of Ireland, with an executive responsible to that parliament. This is the whole basis of the Treaty. It is the bedrock from which our status springs, and any later Act of the British Parliament derives its force from the Treaty only. We have got the present position by virtue of the Treaty, and any forthcoming Act of the British Legislature will, likewise, be by virtue of the Treaty. It is not the definition of any status which would secure to us that status, but our power to make secure, and to increase what we have gained; yet, obtaining by the Treaty the constitutional status of Canada, and that status being one of freedom and equality, we are free to take advantage of that status, and we shall set up our Constitution on independent Irish lines.

No conditions mentioned afterwards in the Treaty can affect or detract from the powers which the mention of that status in the Treaty gives us, especially when it has been proved, has been made good, by the withdrawal out of Ireland of English authority of every kind. In fact England has renounced all right to govern Ireland, and the withdrawal of her forces is the proof of this. With the evacuation secured by the Treaty has come the end of British rule in Ireland. No foreigner will be able to intervene between our Government and our people. Not a single British soldier, nor a single British official, will ever step again upon our shores, except as guests of a free people

Child page (sample)

Text here

My Sample Post

Galway Castle

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Integer elementum eleifend dolor, et accumsan elit efficitur nec. Sed nec interdum felis. Aliquam nisl magna, accumsan nec facilisis tincidunt, tempor a mi. Mauris fermentum dolor vel mauris fermentum lacinia. Ut laoreet tortor sed urna pellentesque molestie. Aenean in mollis augue. Donec massa nisi, fermentum non ligula id, auctor dictum magna. Sed scelerisque nec turpis rhoncus rhoncus. Etiam venenatis et ex eget vehicula. Aliquam erat volutpat. Duis ac orci massa. Nulla varius cursus eros. Ut sit amet bibendum est.

Donec orci lacus, commodo vel sapien non, tincidunt bibendum ex. Etiam ut purus rutrum, pellentesque tortor id, cursus lacus. Cras suscipit nisi et odio tempus vestibulum. Pellentesque tempus odio non hendrerit placerat. Cras pretium vulputate pretium. Sed nec odio convallis, laoreet libero vel, elementum metus. Nam posuere facilisis magna, quis laoreet orci molestie non. Aenean ante purus, laoreet ac neque ac, bibendum placerat velit. Duis hendrerit, elit et aliquam tincidunt, orci tortor egestas ex, sed volutpat mauris lectus id massa. Cras quis pharetra sem. Aliquam enim nulla, feugiat eget fermentum a, aliquet ac risus. Maecenas quis congue magna. Ut accumsan, augue in tristique euismod, risus enim dictum justo, non mattis ex magna at est. Duis quam sapien, vestibulum quis ex consequat, gravida bibendum purus.

Praesent nec aliquam felis. Nulla mollis in nisi nec imperdiet. Nam in sagittis mauris. Donec vel velit tincidunt, mollis lorem ut, fermentum erat. Nulla elementum pretium nibh. Ut vulputate diam non elit sagittis elementum eget interdum tellus. Morbi consequat felis in ex tristique, ac convallis metus viverra.

Donec in justo a mauris imperdiet mollis. Suspendisse bibendum ullamcorper ex id tempus. Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Nullam sapien felis, commodo sed egestas et, luctus in purus. Vestibulum nec purus lectus. Mauris eu lacus quis eros porta tempus vitae id purus. Quisque a lacus quis nulla tempor tempor nec id ex. Morbi nec nisi sem. Suspendisse mattis elit enim, ac congue felis facilisis non. Duis molestie rhoncus diam, ut sodales lectus rhoncus nec. Vivamus lectus ligula, ultrices in massa hendrerit, maximus ultrices urna. Ut turpis dolor, rhoncus pellentesque purus nec, sagittis mattis metus. Duis eu justo sagittis, ornare augue eget, facilisis libero. Curabitur at tempus urna. Pellentesque vel nulla tincidunt, ultrices ex semper, dapibus mauris. Ut vulputate accumsan libero in hendrerit.

Pellentesque dignissim sollicitudin elit, quis vestibulum magna tempus a. Etiam ultricies leo dolor, vel viverra lorem laoreet quis. Suspendisse potenti. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nunc commodo magna et felis interdum, dignissim ornare metus placerat. Phasellus ut ligula nisi. Nullam vitae vehicula dolor. Aliquam elit diam, consectetur at sodales pellentesque, finibus non quam. Morbi laoreet leo sed orci condimentum, in vulputate massa pulvinar. Sed tempus nisl ut accumsan fringilla. Morbi nec purus sit amet velit ornare finibus.

Seamus Heaney

Here’s a link to the extensive coverage of Seamus Heaney in today’s Irish Times and the Guardian. The Guardian also has links to Heaney reading several of his works here.