The biting irony comes right out at the listener as soon as they notice the title. “Law and Order” certainly does not agree with Stiff Little Fingers’ depiction of the police force emasculating and attacking the locals and friends portrayed in the song. Through this improper use of emasculating violence comes a feeling of isolation, constant berating causing discomfort an alienation on one’s own home turf.

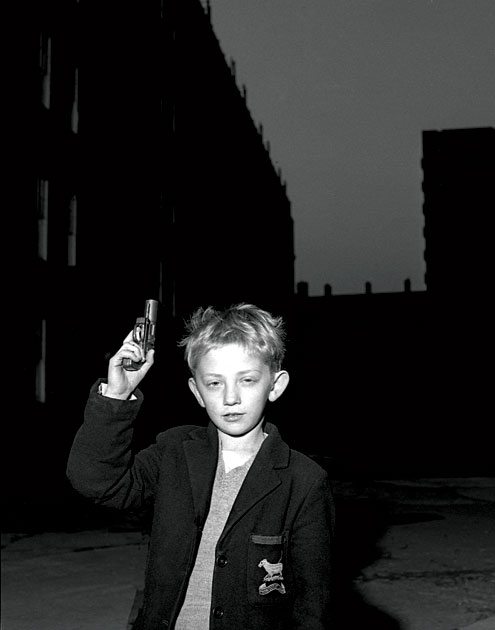

The ‘law’ here does not really uphold law, order or justice. They dispense anarchic violence; the police spend their time abusing those that do not have the status and power they hold: “I had a friend who was lifted by the law… They treated him like shit / Kicked him in the head and laughed when he bled / spat in his face and pulled his hair.” Whereas the violence portrayed in Kendrick Lamar’s tracks like ”Sing About Me” and “m.A.A.d City” revolves around guns, the violence portrayed here seems personal and vicious from the proximity. This is not pulling a trigger anymore but getting your hands on someone else. The street justice of Compton is not even this disordered, even though those that carry this out are supposed to be the figures of law and order – this is the critique that Stiff Little Fingers makes.

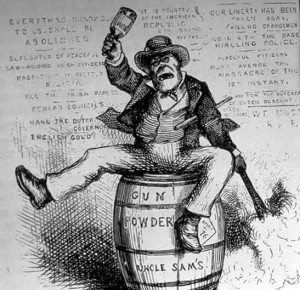

Through this violence comes feelings of not being welcome, consequently creating feelings of isolation. The same situation occurs in Bernard MacLaverty’s Cal with the titular character being burned out of his home and threatened by people who are on both sides of a war Cal wants no part of. Cal often feels alone due to these outside forces, this sense of unfairness and Stiff Little Fingers orate this struggle with confidence. “I don’t think like you” and “you’re just a pawn in their game / just another number you aint got no name” describes an individual struggling against the situation around him, not really fitting into the system.

Violence is forced on Cal just as it is forced on the innocents of “Law and Order” and the man in “No More of That.” All of these characters are isolated by their horrible situations. Stiff Little Fingers does not offer a solution to this isolation caused by unfair violence; they only offer their view that the situation “isn’t fair”, that with the current situation “there’s o justice in it / None!”

[If you would like to refresh your interactive experience please pinback to the songs.]