The Clancy Brothers: Their Contributions to the American Folk Music Revival, and the Irish Folk Tradition

Source: http://www.thekilkennys.com/a-tribute-to-the-clancy-brothers-by-the-kilkennys

The contributions of the Clancy Brothers to Irish and American folk music cannot be understated. They were the strongest Irish folk presence in the American Folk Music Revival of the 1950’s and 1960’s, and their influence on this movement was immense. Their influence in Ireland was of even greater importance, as they gained popularity during a time in which traditional folk music had been mostly forgotten in the country. This paper will give a brief history of the Clancy Brothers, then go on to discuss their influence on the American folk scene of the 1950’s and 1960’s, and finally discuss the Clancy Brothers’ crucial role in revitalizing traditional folk music in Ireland. Also attached to this project is an arrangement for a cappella performance of a well known song performed by the Clancy Brothers, “Wild Mountain Thyme,” (alternatively known as “Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go). A brief description of the arrangement process will also be included.

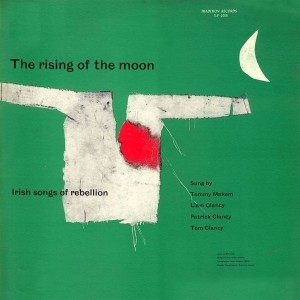

The Clancy Brothers, from Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary, grew up in a musical household. Liam Clancy recalls in his autobiography The Mountain of the Women: Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour,” his father entertaining them by singing songs from Italian operas. He also mentions that his father was singing in gibberish, although his vocals were very good (Clancy, 30). After traveling Ireland for a period of time recording traditional music with an American musicologist (during which time he first met future musical collaborator Tommy Makem) and performing in theatrical roles, Liam Clancy left Ireland to join his brothers, Tommy and Paddy, in New York. After becoming acquainted with the New York folk music scene, The Clancy Brothers met up with Tommy Makem and formed a record label called Tradition Records. The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem recorded their first album, The Rising of the Moon for this label. Liam Clancy bemoans the group’s first effort in his autobiography, saying “the album was a bunch of songs belted out in unison by four raw voices with occasional accompaniment from Paddy’s harmonica… to us it was just plain embarrassing” (Clancy 145). However, the album was well received by the very few that heard it. Tradition Records was a success, and the label began producing albums from up and coming folk stars, including Odetta, Alan Lomax, and the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem themselves. During this time, before The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem truly took off as a musical group, the members were pursuing careers as actors. However, the group began to come together as a musical act after the release of their album Come Fill Your Glass With Us, a collection of Irish drinking songs. At this point, although they continued acting, the group members seemed to begin to stop viewing themselves as actors who dabbled in singing. This album led to the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem being booked for the first time for performances around Greenwich Village. The group was even booked in a club in Chicago, where they ended up spending a month playing shows (Clancy 235). Before long, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem became regulars of the Greenwich Village club scene. They found managers and began to make a name for themselves in the area. The group continued to gain momentum, and in January 1961, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show (Clancy 280). While their popularity was secured in the United States, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were still unknown in Ireland. This changed when a popular Irish radio broadcaster, Ciarán Mac Mathúna came to America and returned with several of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s albums. He played the albums on his radio program, and soon group became a sensation in their native Ireland. With the help of Ciarán Mac Mathúna, a tour of Ireland was organized. Tommy Makem recalls how he and the Clancy Brothers did not know what to expect from their first concert. To everyone’s relief, the crowd was welcoming, the venue was packed, and there were even people who would not fit in the venue standing outside (Makem). The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s popularity in Ireland soared, and in 1964, one third of all records sold in Ireland were The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem records (“The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem: History”). The late 1960’s and the 1970’s saw several departures and lineup changes within the group. Tommy Makem left in 1969 to pursue a solo career. Bobby Clancy, the brother who had stayed in Ireland, replaced him. After another round of lineup changes, Liam Clancy left the group in 1974, and reunited with Tommy Makem as Makem and Clancy. The duo performed together for 13 years. In 1990, Tom Clancy died, and in 1991, after an amicable split from Tommy Makem, Liam returned to the Clancy Brothers. The rest of the 1990’s saw a myriad of lineup changes, and the deaths of Paddy Clancy in 1998. In 2002, Bobby Clancy died, and four years later, Tommy Makem also passed. Now the last remaining member of The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, Liam Clancy remained musically active until his death in 2009 (“The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem: History”).

Source: http://clancybrothersandtommymakem.com/cbtm_d10_rising.htm

Source: http://www.flickriver.com/photos/bpfallon/tags/thepogues/

The Clancy Brothers, with what was at the time considered their “exotic” style and influences, significantly affected the American Folk Revival. They were the first Irish act to arrive on the American Folk scene. Their adaptations of Irish folk tunes were accessible to an American audience (Motherway, 91). Throughout their time spent immersed in the Greenwich Village folk scene, they shared their type of music with numerous up and coming musicians. They met and befriended many of these musicians including Pete Seeger, a leader of the American Folk Revival, whom the Clancy Brothers enlisted to play banjo on one of their albums. They also met American folk legend Woody Guthrie after a benefit for Guthrie, who was permanently hospitalized with Huntington’s disease. Liam Clancy recalls, “It was a sad way to meet a great soul for the first and last time” (Clancy, 144). Through Tradition Records, the label that the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem ran, the group formed connections with an extensive list of folk musicians, including Odetta, John Jacob Niles, Etta Baker, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Woody Guthrie’s collaborator Cisco Houston, and the famed American musicologist and collector of folk music Alan Lomax (Clancy, 119-120). However, the musician that the Clancy Brothers seemed to have had the most significant influence on is Bob Dylan. Liam Clancy said of Dylan, “Everywhere you went in the Village this young, restless, fidgeting kid seemed to be there… we got to like him and we started hanging out together at the Village parties” (Clancy, 257). Supposedly, it was the Clancy Brothers who gave Dylan his first break by suggesting him to John Hammond of Columbia Records to fill in as a harmonica player for a recording session. Shortly thereafter, Dylan signed with Columbia records, and Hammond served as his producer (“Clancy Brothers Influence”). Dylan considers the Clancy Brothers, specifically Liam, to be one of his biggest influences and heroes. He says in the documentary No Direction Home, “What I heard in the Clancy Brothers was rousing rebel songs, napoleonic in scope. They were just these musketeer type characters. And on the other level, you had the romantic ballads that would just [show] the sweetness of Tommy Makem and Liam” (No Direction Home). After joining Dylan on stage to perform “When The Ship Comes In” for Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert, Liam Clancy allegedly suggested to Dylan that the Clancy Brothers record an album of Dylan’s songs in an Irish style. When he asked for Dylan’s permission, Dylan is reported to have said, “You still don’t get it do you Liam? You’re my heroes man, my heroes” (“Clancy Brothers Influence”). In addition to their influence on certain musicians, the Clancy Brothers success garnered interest in Irish folk music among American audiences. Susan Motherway argues that the Clancy’s political themes provided further interest in the group’s songs. She says of the Clancy’s success, “They soon recognized a market for the performance of the Irish political songs in America and formed a ballad group. Their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show (1961) prompted the explosion of an Irish folk movement led by the Dubliners, the Wolfe Tones, and the Johnstons” (Motherway 143). Motherway also asserts that, by performing politically charged Irish songs in an international context, the Clancy Brothers connected to minority and civil rights movements in America (Motherway, 8-9).

THE CLANCY BROTHERS – When The Ship Comes In… by giemmevu

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makemperforming Bob Dylan’s “When the Ship Comes In” at his 30th anniversary celebration concert.

The Clancy Brothers’ influence on their native Ireland was even more significant than their influence on American folk music. Many scholars credit the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem with the revival of Irish folk music in Ireland in the early 1960’s. Susan Motherway describes a lack of pride in traditional Irish music in Ireland prior to the Clancy Brothers’ boom in popularity. The Irish folk revival that the Clancy Brothers started restored this pride. She cites Tommy Sands’ The Songman: A Journey in Irish Music, in which Sands states, “[Irish radio]was realising that the future was empty without the riches of the past” (Motherway, 144). Tommy Makem himself states “The entire population of the country had rediscovered their own songs and music. Suddenly realizing that their own culture was as good as, and, in some cases, better than most of what they had been hearing on the radio, the nation’s enthusiasm knew no bounds” (Makem). Getting more at the political influence that the Clancy Brothers had, Susan Motherway quotes Christy Moore, stating, “Christy Moore believed that the Clancy Brothers provided the Irish people with a modern expression of Irishness that enabled them ‘to cast off the shackles of conservative Catholicism and to break free from the dark sentence that Mother Church had read out.’ Christy believes that the Clancy Brothers and the Irish folk revival that ensued revoked the ideals of De Valera, rediscovered a wealth of culture, and renewed a pride in Irish culture and, particularly, music” (Motherway, 144). The Clancy Brothers rebel songs and politically charged ballads made their music more relevant than ever during the height of their popularity, as this coincided with the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Their lyrics were even more significant because Tommy Makem, one of the group members, was himself from Northern Ireland (Motherway 143-144). The Clancy Brothers had become a cultural phenomenon in Ireland. For instance, Aran sweaters, the trademark costume of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, experienced a huge worldwide rise in popularity after the Clancy Brothers appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, supposedly having a sales increase of 700%. The extent of their popularity can be seen in the fact that one third of record sales in Ireland in 1964 were The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem records (“The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem: History”).

The following is an arrangement, for a cappella performance, of one of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s songs, “Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go,” alternatively titled “Wild Mountain Thyme.” Attached is a video of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s performance of the song, a PDF containing the sheet music of the arrangement, and an mp3 of the arrangement (from the playback produced by the arranging software). I am a member of one of Geneseo’s a cappella groups, and have been arranging some of the music for the group for about a year. It is an activity that I enjoy, and I had actually planned to arrange this piece for my own amusement before I ever considered making it part of this project. A cappella means a vocal performance without instrumental accompaniment As such, in a typical a cappella arrangement, one singer will sing the solo, and the remaining singers will provide vocal harmony and accompaniment. In this case, I have arranged the piece for performance by a group consisting of a baritone soloist, and four additional voice parts: sopranos, altos, tenors, and basses. I used the program Finale Songwriter to arrange this piece. The first step in arranging is to become very familiar with the song in question by listening to it repeatedly, and determining the chords of the song. Next, I transcribed the vocal solo into Finale. After this point, the arranging process is very open. The arranger can interpret the song any way they please. My arrangement is not a particularly faithful adaptation of the Clancy Brothers’ version of the song, and this was a stylistic choice. One of the biggest challenges that this arrangement posed was the fact that, in the Clancy Brothers’ performance, there really isn’t a lot going on. For a good portion of the song, the melody is sung by several voices in unison. In certain parts, there is one voice singing a line of harmony. Instrumentally, there is very little going on. A guitar and banjo are strumming chords, and a harmonica is playing the melody. It is a very simple song, carried primarily by the voices of the singers and the pleasing melody. It was challenging to make this song interesting for a cappella performance, and doing so required some changes to the song. For the most part, this consisted of adding additional lines of harmony, and filling in the remaining voice parts with notes from the chords played by the guitar and banjo. The final step in arranging this piece was assigning lyrics or syllables to the notes. Typically in a cappella performance, it is common for the accompaniment voice parts to sing non-word syllables like “do,” “dim,” “oh,” “ah,” etc. In this case, I wanted to make the piece sound more choral, and decided to primarily have all of the voice parts sing some of the lyrics of the song.

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem performing “Will Ye Go, Lassie Go.”

PDF of the arrangement.

Audio produced by the arranging software