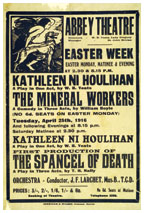

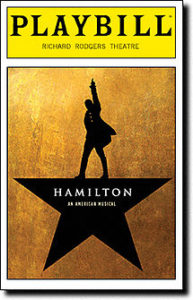

What does Hamilton have to do with Cathleen Ni Houlihan? Hamilton, a block-busting critical-darling rap opera about one of the least renowned Founding Fathers staged by an all-minority cast in 2015, seems completely removed from the austere symbolist drama written by William Butler Yeats and the aristocratic Lady Gregory in 1902 to inspire Irish nationalism. The differences hardly end there. Genre, context, idiom, characterization, and production all differ. So can you get to Broadway from Lower Abbey Street?

Historical memory ties these works together. An omnipresent bank of societally-specific received narratives, images, and rituals, historical memories interpret past events certain ways for certain groups. They are selective, exclusionary, and frequently unrecognized by those who prescribe to them. Yet collective memories underpin national identity. They define ‘us’ versus ‘them.’ And they prescribe how individuals should act by confirming that they are who they already believed they were. By taking plays from three different dramatic genres united by the subject of colonial rebellion, this site demonstrates how founding myths reaffirm a nation’s identity. The ‘Context’ page introduces the plays that will be discussed throughout the site by genre and offers some historical and literary background. ‘Memory’ discusses the concept of historical memory and examines the particular narratives of collective suffering and martyrdom which reoccur throughout plays dealing with rebellion. Narratives derived from a collective memory inform that nation’s identity. The section labeled ‘Identity’ shows how cliches surrounding national remembrances of rebellion reaffirm collective identity. Not everyone shares a nation’s collective memory, however. ‘Reception’ examines how historical memory can be both political and exclusive. Beginning with ‘Context’, visitors can navigate this site vertically, seeing how plays from a certain genre relate to historical memory, identity, and reception. Or the site can be explored horizontally by following the concepts ‘Memory,’ ‘Identity,’ and ‘Reception’ across the three genres.

Other than the novelty of comparing Hamilton and Cathleen Ni Houlihan, what does this project offer? Why put these two plays into dialogue? Drama as a literary form is particularly well suited for the transmission of historical memory: “All memories…only assume collective relevance when they are structured, represented, and used in a social setting.”[1] Memory studies frequently focus on individual writings such as letters or diaries and literary forms such as autobiography or poetry which only reach a limited audience. Dramas often become popular because they lack the individuality of these other forms. But this makes them more representative of collective attitudes. By combining narrative, language, image, and setting, drama can also express a greater variety of collective memories than purely textual works. Audience reaction to certain works attaches a social referent to those memories, allowing a critic to gauge who prescribes to them. Comparing works from different periods demonstrates both the plasticity of the past, which is continually reinterpreted to suit contemporary needs, and the stability of certain collective memories ingrained in a nation’s identity. It also shows that historical memories function in similar ways regardless of particular social contexts.

Find background information about the works in discussion here: Context

Find information about the ways in which memory is presented in historical drama here: Memory

Find information regarding the function of identity in historical drama: Identity

Find how the works in discussion affected the public and how they were received here: Reception

For further research, here are the sources used: Sources

[1] Wulf Kansteiner, “Finding Meaning in Memory: A Methodological Critique of Collective Memory Studies,” Theory and History 41, no. 2 (May 2002): 190.