“My sons were faithful and they fought.”- Patrick Pearse, The Mother (1915)

The Rising in Dublin began with the seizure and occupation of the General Post Office by the Irish Republicans the morning of Easter Monday, April 24th, 1916. Around the city other contingents attempted to take control of various, pre-designated targets. They captured St. Stephen’s Green, the Four Courts, Boland’s Mill, Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, the South Dublin Union and they also began fortifying buildings overlooking key bridges and roads that lead into the heart of the city (1). In general, the style of defense they used is the pre-World War I doctrine of strongpoint defense.

True to the belief that Rising represented a microcosm of World War I, one of the first British responses to the Volunteers’ occupation of the GPO was to send a cavalry unit, the 6th Reserve Cavalry to confirm this. When the lancers arrived on the scene they found the building in possession of the Irish and they led a doomed charge down Sackville Street. As was the case in 1914, the cavalry charge against a fortified position was easily rebuffed, leaving four dead horsemen in the street (2).

As the British infantry in Dublin began to respond to the Rising, they found an inherent weakness of the “strongpoint system” being utilized in an urban environment. Generally, though the pockets of Irish defense were rather strong and difficult to attack frontally, there were numerous “passive zones” (3) in which there was no real defense and that the British could move through without harassment. Without interlocking fields of fire defending these passive zones, the defense of Dublin was doomed.

Perhaps one of the greatest blunders by the Volunteers was their overlooking of railway bridges and train stations. Small squads of men could have been sent to destroy the rail bridges leading into Dublin from every direction. This would have greatly hindered the movement of British reinforcements into the city. Instead, the same day as the rebellion started, government forces from Curragh began to arrive in Dublin to supplement those forces already inside the city (4).

Yet another tactical miscue of the rebel battle plan was the occupation of St. Stephen’s Green, a park inside of Dublin. Though this could have been written off as important symbolism for the Catholics, the park was surrounded by tall hotels and other multistory buildings that the British quickly occupied and began using to fire into the rebel positions (5). It is generally believed to be common tactical sense to occupy the high ground, yet here the Volunteers displayed none and instead put themselves at a grave disadvantage. Seeing this however, they surrendered their position here and moved to the Royal College of Surgeons(6).

From here the system of battle can be seen as a British noose, slowly being tightened around the isolated Irish positions. Due to the lack of manpower, the strongpoint system that the Irish leaders have chosen to use quickly showed its flaws. Yet the British were still using pre-war tactics throughout and using only infantry and machine guns in their attacks on rebel positions and as such were rebuffed at more densely defended points. Seeing this, they began using an 18-pounder field gun battery at Grangegorman Asylum to bombard rebel positions, quickly turning the battle in their favor (7).

Near the end of the day on Tuesday, April 25th, the British gunboat HMS Helga moved up an unblocked River Liffey and began firing on Volunteer positions at Boland’s Mill (8). With essentially a mobile artillery battery on the River Liffey, the Volunteer positions throughout the city were now in serious danger as they had nothing to combat this new threat with. Throughout the week the Helga (joined the next day by HMS Seahawk) and other British artillery leveled much of city around the GPO, using a continual annihilating fire to smash rebel positions (9). Total war was being waged in downtown Dublin.

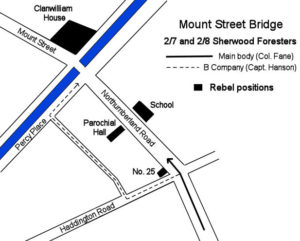

On Wednesday, April 26th, a small Republican force guarding Northumberland Road and Mount Street Bridge opened fire on densely packed British formations. They had blundered into a Volunteer strongpoint in parade formation and suffered heavy casualties throughout the day. One of these houses forming the defensive bloc, 25 Northumberland Road was guarded by only two men, who managed to resist British attacks for almost five hours (10). Despite significant losses, the British continued to attempt frontal infantry assaults and lost yet more men, the lessons of 1914 had apparently been forgotten. In the end, the British overcame this position but not before losing almost 250 men (11).

By Thursday, the British had begun using improvised armored cars to move their men and material more safely throughout the city. That same day a British shell hit the Irish Times building and ignited a fire that consumed much of Sackville Street (12). The British forces now had the Volunteers surrounded at just about every position and use of incendiary shells made the defensive position untenable for the Republican forces. Though heavy gunfighting continued into Saturday, the tactical battle for Dublin was effectively ended Friday. Superior British numbers and use of artillery proved far too much for the Volunteers to be able to resist. However the British willingness to use total war tactics in an urban center soon turned popular Irish sentiment against supporting the English war effort.

- RTE, “Chronology of the Easter Rising.”

- Ibid.

- Henri Lucas, Pascal Marie, The Evolution of Tactical Ideals in France and Germany during the War of 1914-1918. 1923, pg. 27.

- RTE, “Chronology of the Easter Rising.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 1916 Rebellion Handbook, N.p.: Irish Weekly Times, 1916, pg. 99.

- RTE, “Chronology of the Easter Rising.”