Both 1776 and Hamilton use clichés but the latter does so in a much more interesting way than the former. One cliché they jointly exploit is the ideological drive of their main characters against counterproductive factionalism. An unnatural energy and commitment to the principles of liberty and democracy animate both John Adams and Alexander Hamilton. They struggle through petty partisanship and personality differences to create a fundamentally sound political system. Whatever disagreements may arise, they can ultimately be resolved for the betterment of the nation.

1776’s main use of historical memory, however, centers around the drafting and passage of the Declaration of Independence. It confirms the association of this document with the true birth of the nation. America became America in 1776, not in 1783 or 1787 (or 1865). This historical memory comes at the expense of actual history. Drafting the Declaration was viewed as less important at the time compared to writing state constitutions or securing international support for the war. The early republic celebrated the document more for its denouncement of British tyranny rather than as a beacon of liberty. ‘The Egg” also pairs the debate over the Declaration with a discussion of the national bird, the creation of the national symbol of the eagle. While Franklin associates the eagle with “European mischief,” the issue is quickly forgotten. Produced during the Vietnam War, the play reassures its audience that American power has always been fundamentally just since it rests on the ideals expressed in the Declaration. The play as a whole supports a widely-held but historically controversial belief: the American Revolution was indeed revolutionary.

Despite the use of contemporary idioms and a racially diverse cast, Hamilton supports several cliché about the American character. The most obvious is the projection of a Horatio Alger ‘ragged Dick’ figure onto Alexander Hamilton. The play’s opening lines announce this theme: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore…grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” All his achievements can be attributed to his own innate qualities. He is industrious, enterprising, and smart. Despite initial adversity, his perseverance and self-confidence will pay off. His personal qualities reflect those of the nation: “I’m just like my country, I’m young, scrappy, and hungry, and I’m not throwing away my shot!” Like the melodramas, Hamilton locates the source of conflict outside the individual, either with England or Hamilton’s political rivals Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. Highlighting Hamilton’s West Indian birth reinforces both the cliché of America as a land of opportunity and as receptive to immigrants. Later on, Hamilton and Lafayette reflect on their status as immigrants before the battle of Yorktown, affirming together: “[Immigrants] get the job gone.” The play does portray disagreement over the creation of the nation. But focusing on Hamilton confirms how Americans like to view themselves.

While Hamilton taps into an American national identity, it also engages with African American collective memories. Significantly, a white actor, Jonathan Groff, played the role of George III in the original Broadway production. Reimaging the Founders as minorities resisting the tyranny of a white master and winning provides a sense of catharsis, especially in regards to the victimization of African Americans by public authority figures. Public awareness of this victimization has grown in recent years. But it represents a narrative Black Americans have long understood to be true. O’Casey may have sought a similar ex post facto catharsis by ridiculing the ideology of the 1916 leaders. Dublin’s working class is too shrewd to believe Independence would change anything. Hamilton’s emphasis on the eponymous character’s antislavery sympathies also reaffirms the myth that social and racial equality underpinned the Revolution. Adams, Franklin, and Jefferson struggle with the issue of slavery in 1776. Adams affirms slaves are Americans: “They’re people and they’re here.” But they concede to slave interests for the good of the nation as a whole. Sacrifice the individual so the nation can live. Hamilton as an antislavery advocate, however, does not reflect a collective memory. It attempts to create one. Who knew Alexander Hamilton opposed slavery other than scholars before this play?

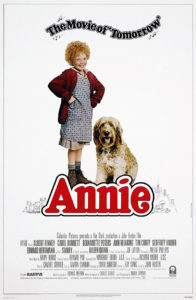

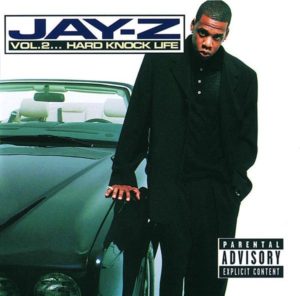

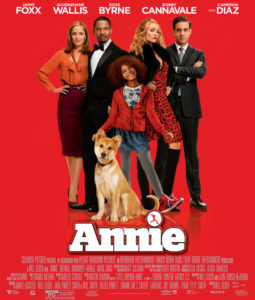

Rap aligns Hamilton with the cultural experience of African Americans more so than the actual casting of minorities. The play could be staged with an all-white cast. But the idioms used in the work identify it with Black America. Rap derives its appeal by being subversive. It reworks mainstream musical material into a unique, often culturally-specific expression. Little Orphan Annie’s “Hard Knock Life” becomes Jay Z’s anthem about growing up in the ghetto. Hamilton reverses this process. It inserts a traditionally subversive art form, rap, into a mainstream vehicle, the musical. When considered in relation to its subject matter, this reversal serves to integrate African Americans into the cultural memory of the nation as a whole. Hamilton is not unique in this. Recasting The Wizard of Oz or Annie with minorities signals their inclusion in America’s cultural memory, specifically in narratives of struggle and opportunity. Yeats and Lady Gregory do the same thing in Cathleen Ni Houlihan. They take a culturally-specific art form, high drama, use it to demonstrate their engagement with collective memories, and thereby align their minority identity with the nation as a whole.

Identity and Political Melodramas