On April 10, 1998, the Belfast Agreement, also known as the Good Friday Agreement, was signed.

This three-way agreement between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, Northern Ireland, and the Government of Ireland promoted cross-border relations between the North and South. In the Declaration of Support, it states “it is accepted that all of the institutional and constitutional arrangements – an Assembly in Northern Ireland, a North/South Ministerial Council, implementation bodies, a British-Irish Council and a British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and any amendments to British Acts of Parliament and the Constitution of Ireland – are interlocking and interdependent and that in particular the functioning of the Assembly and the North/South Council are so closely inter-related that the success of each depends on that of the other” (1).

This idea that both sides had to work together in order for this agreement to really have an impact was monumental. By splitting the power up and also making it so that the North and South were interdependent it allowed the two countries to resolve disagreements in a peaceful and non-violent manner. In a civil way, it gave a voice to both sides. One way that the Agreement encouraged the power sharing between the two groups was to find common ground where they can work together to better the land as a whole. This included areas such as agriculture, transportation, education, waterways, and things of that nature. Overall, there were twelve areas total where the North and South had to work together. This helps with the flow of cross-border connections. Instead of focusing on the differences between Irish Catholics and English Protestants, they can focus on the common interests that can better the nation and hopefully help the people feel more connected to one another. It builds a sense of community and attempts to break the imagined border between the Irish Catholics and English Protestants.

The agreement also allowed the people of Northern Ireland to remain with Great Britain if the majority of the population agreed to it on their own terms. This statement was a compromise between the Irish Catholics and English Protestants wishes; it did not set anything in stone and respected the wishes of both sides. This was to encouraged Irish Catholics to use more peaceful means to achieve their dreams of a united Ireland. “It is the firm will of the Irish nation, in harmony and friendship, to unite all the people who share the territory of the island of Ireland, in all the diversity of their identities and traditions, recognising that a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island” (1).

What Were the Initial Reactions to the Belfast Agreement?

The reactions to the Agreement were mixed at first. Both sides were critical and complained that the Agreement gave too much to the other side. For the English Protestants, they worried that if the population of Northern Ireland were somehow persuaded into joining the Republic, they would lose their connection with Britain. They also feared about becoming the minority in a vastly Irish Catholic nation. The Irish Catholics felt that they would never achieve a united Ireland if they had to somehow convince the mostly English Protestant nation to join the Republic through peaceful means alone.

Thanks to the Agreement, however, citizens are free to reside where they choose, so segregation with Northern Ireland was working towards more integration between communities and embracing the diversity. While the Agreement appeared to be successful with addressing the issue of the border, it needed more time and the efforts of the citizens in order for the boundaries to be settled.

It’s hard to ask citizens to leave the past behind them and settle their differences when it is so deeply embedded in their historical memory. Events like, Bloody Sunday, established borders through violence and led to mistrust between Irish Catholics and English Protestants. This mistrust and hatred between the two groups led to boundaries between them where certain areas, such as Shankill Road, within Northern Ireland were clearly defined as Catholic or Protestant with the use of graffiti, murals, and movements like Orange Parades. It was evident that Irish Catholics and English Protestants still had trouble trusting one another. On top of that, there was also some controversy with the releasing of prisoners who were involved in the violence during The Troubles and during the arrangement of The Agreement the IRA was refusing to give up their weapons. Because of these reasons and past events, both Catholics and Protestants were extremely doubtful of The Agreement’s success.

While cultural boundaries were more difficult to overcome because of historical memory, physical borders themselves were easier to control.

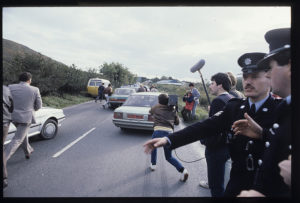

As seen in the first image above, the border was policed through the use of the military and police. People could not freely cross the orders without being subjected to searches and checkpoints due to mistrust between Irish Catholics and English Protestants.

However, as the years went on, it became easier to cross borders more freely because of the demilitarization of borders. As seen in the second image, there is no checkpoint or military personnel indicating that one is entering or exiting Northern Ireland. The only indication is a speed sign. “Crossing the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic used to involve delays, checkpoints, bureaucratic harassment and the lurking threat of violence. That it’s now virtually seamless — that you can drive across without even knowing it — feels close to miraculous” (2). While this process did take a while, it does show that the Belfast Agreement was successful in achieving peaceful borders that did not require armed guards or checkpoints.

By opening borders and disarming potentially threatening groups, this helped the North and South become more connected and feel less threaten by each other. “This city, this country, is like a woman who has given birth,” Mr. Lynn said. “All the trauma, the pain and the fighting are over. We’ve come out of the Troubles — out of black and white and into color” (2).

Although the Belfast Agreement was not a perfect peace treaty, it did its best to acknowledge major issues and dealt with it as best as it could. It tries it’s best to give both sides a voice and stressed the importance of cross-border relations. However, it was a difficult situation where there was no clear answer.

In order to keep the peace, the North and South must recognize and respect their differences and also find common ground where they can work together towards a brighter future for the entire land as a whole.

1. Northern Ireland Office. “The Belfast Agreement.” GOV.UK, 10 April 1998, www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-belfast-agreement.

2. Lyall, Sarah. “On Irish Border, Worries That ‘Brexit’ Will Undo a Hard-Won Peace.” The New York Times, 5 August 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/08/05/world/europe/brexit-northern-ireland-ireland.html?action=click&module=RelatedCoverage&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer.