Ireland officially split in 1920, forming Northern Ireland. The Government of Ireland Act was created amidst the violent War of Independence in an attempt to quell the IRA and Nationalist anger and satisfy the small Protestant population while still maintaining control of the entire isle. The twenty-six southern counties would have a Home Rule parliament (self-governance), and the six north-eastern counties would have a devolved parliament and send MPs to Westminster. Ulster Unionists accepted the separation and Northern Ireland was created; however, the Irish nationalists spurned the continued British presence and kept fighting for independence until the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921.

The remains of British bombing in Cork during the Irish War of Independence.

In Northern Ireland, the Unionist party leaders were convinced that unless the government was firmly and irrevocably in the hands of the Protestants, Northern Ireland would not last. Following the initial council elections after the split, the Unionist party controlled ⅔, while the Nationalists held the other third, proving a problem for the Unionist majority. Immediately, James Craig as the first prime minister made motions towards changing the voting system and voting boundaries. In 1922, proportional representation (PR) was terminated, replaced by first-past-the-post, along with the redrawing of the local government boundaries, followed later by the same change in Belfast’s parliament. The gerrymandering lumped large Nationalist-Catholic majorities together so they had the same representation as the smaller Unionist majorities. A good example is the Omagh Rural District Council. For the next election, it was claimed that the 5,381 unionist voters would have 21 seats, but 8,459 nationalists would only have 18. The effect of the gerrymandering in Derry was the most severe. Derry was divided into five wards, three having Unionists majorities, two having Nationalists majorities. The Nationalists wards had larger populations, and yet were counted equally with the three Unionist wards. 9,961 electors secured eight Nationalist councillors, while 7,444 voters secured 12 Unionists councillors.

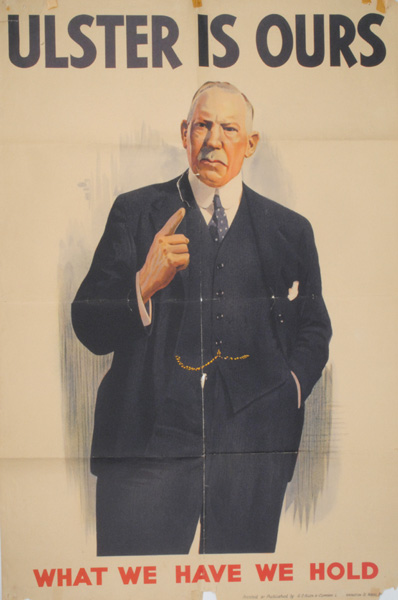

Election poster of James Craig, Northern Ireland’s first Prime Minister, c. 1940.

In addition, the criteria for voters (standing since before 1921) was more likely to apply to Protestants Unionists and exclude Catholic Nationalists. Voting was restricted to owners of a house or tenants and the owner/tenant’s spouse. Grown children still at home were disenfranchised, as were lodgers or older family members. And for the Catholics, it was more likely that there would be multiple adults living in one home unable to vote. Voting rights, or lack thereof, boiled down to one thing: jobs. Most of the better paying jobs went to Protestants instead of Catholics, therefore, fewer Catholics were able to afford homes and were more likely to live with other family members, and thus fewer could vote. It was encouraged by members of government, especially James Craig, PM himself, that the “public [should] employ loyalists–only loyalists”. Sir Basil Brooke would later say of Craig, “He appreciated the great difficulty experienced by some of them in procuring suitable Protestant labour but he would point out that Roman Catholics were endeavouring to get in everywhere. He would appeal to Loyalists therefore, wherever possible, to employ good Protestants lads and lassies”. A 1943 survey would go on to prove just how inequitable the public sector was. In the 55 most senior positions, none were Catholic, and only 37 of 600 middle-ranking posts were held by Catholics. In private companies, it was common that more than 90% of the workforce was Protestant. Unemployment among Catholics was more than double Protestants, only adding to a lack of suffrage for nationalists. And if Catholics and nationalists couldn’t vote, they couldn’t elect others to change policies–it was all too brilliantly done.

Ironically and yet fittingly, the Protestants were fearful of their Catholics counterparts. There was no peace of mind for the Protestants at the beginning of Northern Ireland, no matter how large their majority. They understood that London could never be as staunch in the continuation of the Union as they were, so support was not reliable. It didn’t help that the Catholics were incredibly suspicious in the eyes of the Protestants, especially considering how hard the Catholics had fought the creation of Northern Ireland in the first place. Protestant attitudes were very similar to their predecessors, the English and Scottish settlers from centuries before: they had a bitter wariness, cautious of retaining their hold over Northern Ireland, and unwilling to back down. This went hand in hand with the restraining statues put in place at the very start of Northern Ireland.

Stormont Castle, the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Only 2% of Unionists supported Ireland as a united, independent state, but 38% supported a united Ireland tied to Britain. The general political wheelhouse of the Unionists involved connection to Britain and continued control over Northern Ireland. Those in government passed policies to ensure that Nationalists were shut out of politics, and this pervaded elections for decades. However, some Unionists believed that nationalists could be persuaded to support union with Britain, and 60% thought that the border could disappear as well. Later, Unionists would be devoted to subduing the Catholic rage and promoting peace, but that wouldn’t come until later.

Link to Main Page

Link to Timeline

Suggested next page: Political Structures to Social Anxieties