Not only did women participate in the rising but also Irish children. The Fianna boys consisted of boys and girls from the ages of eight to eighteen. The organization of these children was completely the opposite of the traditional family relationship. The children were sent out for training away from their homes and families. It did not matter what the children’s prior affiliation was before they joined the Fianna Boys. The Fianna accepted all creeds, classes, and parties.[1]

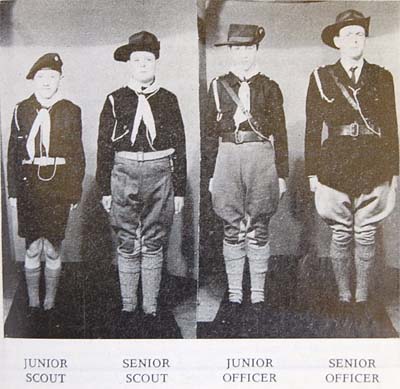

The Fianna wanted to gain independence by training youth. They were involved in both physical and mental training. The Irish language and Irish history were also discussed. Their ideology was to use heroism to overcome oppression.[2] The children learned values of citizenship, discipline, and manliness. They strived for nationalist values and not imperial ones. The group arose around concerns of “the moral and physical degeneration” of the Irish.[3] The Fianna Boys fell under the control of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The Irish Republican Brotherhood increased the military aspect of the Fianna Boys. They trained the boys so they can fight for Ireland when they become men.[4] Being a Fianna Boy was a “sacred duty” to Ireland.[5]

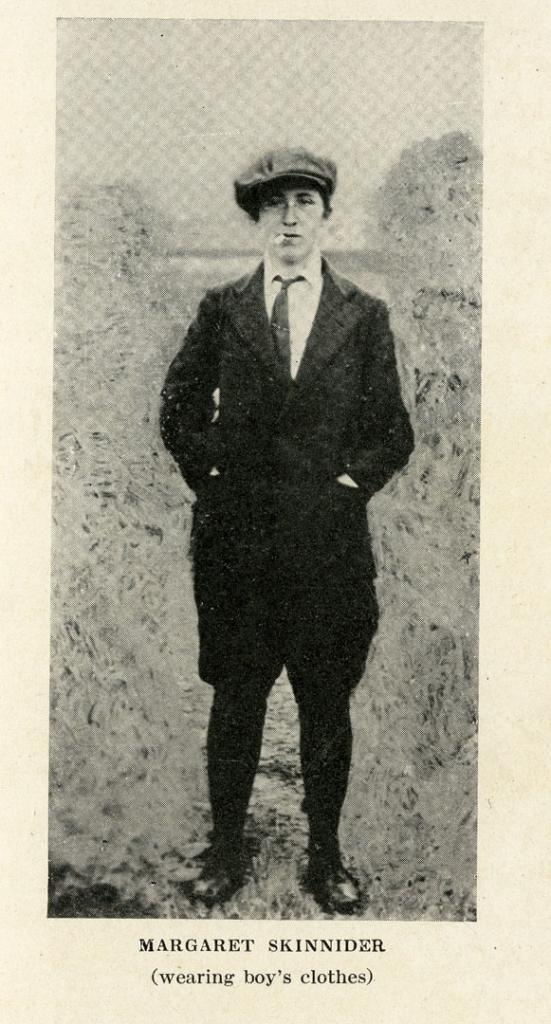

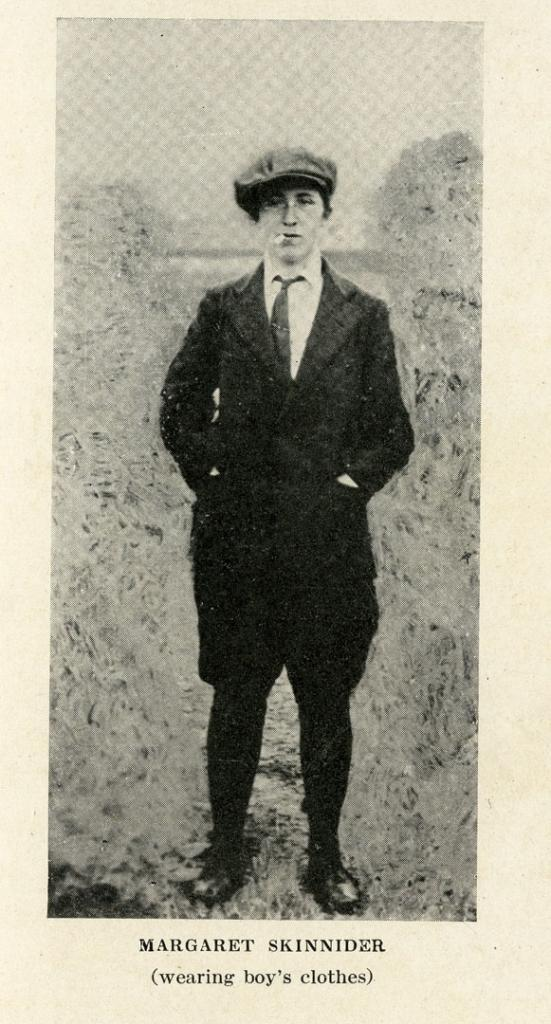

An interesting figure from the Fianna Boys was the Countess Markievicz. She founded the Na Fianna Éireann. She would work closely with the boys. She acted in a motherly role where she cared for and nursed the boys when necessary. She spent a lot of time with them. She lived part-time in Dublin and part-time in Warsaw. She wanted the boy scout movement to be successful.[6] Scouting and shooting were observed regularly at the Countess’s house by Margaret Skinnider. She described the children as young as ten, studying and playing at the Countess’ house.[7] The Fianna was a Gaelic name to invoke the spirit of Ireland, “romance and patriotic tradition.”[8] The boys saved their own money for their uniforms and equipment. She described them as “independent and self-respecting.”[9]

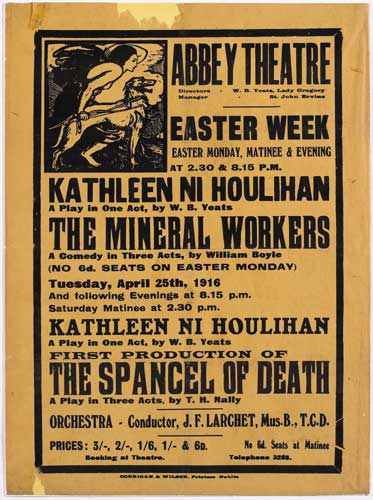

Skinnider also describes an episode where the Fianna Boys held a house for three days. When they were asked how they learned to shoot so well they explained that the Countess taught them every Sunday. Skinnider was dressed up as a Fianna Boy and was able to experience first hand what they did. She walked with them while they asserted their authority.[10] She explained that the Nationalists used the Fianna boys to save Irish men from fighting in the war. Men were out of work because Britain was trying to force them to join the army. The Countess would take children on outings. An example in Skinnider’s memoir was the Countess taking the children to see a play. On this occasion, British officers were present. The Fianna Boys started singing, “The Watch on the Rhine” and the officers responded back with “God Save the King.” “God Save the King” was not socially acceptable at the time and the British were pelted with vegetables and the play was shut down.[11] This struck me as an odd example of the outings that were probably typical with the Countess. Although she is a motherly figure, the Fianna Boys would continue to push the acceptable norms of the British oppressors.

[1] McGarry, 2016. 30.

[2] McGarry, 2016. 31.

[3] McGarry, 2016. 32.

[4] McGarry, 2016. 32.

[5] McGarry, 2016. 33.

[6] Skinnider, 12.

[7] Skinnider, 12.

[8] Skinnider, 23.

[9] Skinnider, 23.

[10] Skinnider, 13.

[11] Skinnider, 15.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Skinnider, Margaret. 2016. Doing My Bit For Ireland (Illustrated Edition). S.l.: Echo Library.

Secondary Sources

McGarry, Fearghal. 2017. The Rising: Ireland: Easter 1916. Oxford: Oxford University Press.