EMILY:

Primary Sources:

Fagan, Terry. Dublin Tenements: Memories of Life in Dublin’s Notorious Tenements. Dublin, IE: North Inner City Publishing, 2013.

Kearns, Kevin Corrigan. Dublin Tenement Life: An Oral History. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2000.

Secondary Sources:

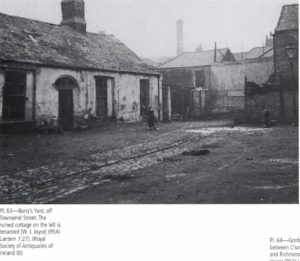

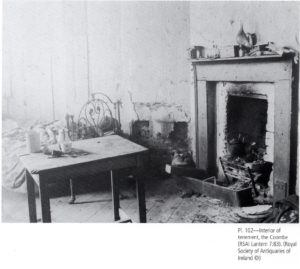

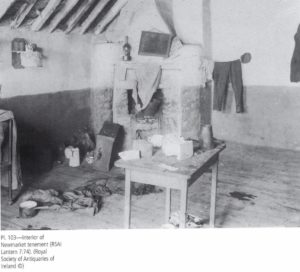

Carlett, Christian. Darkest Dublin: The Story of the Church Street Disaster and a Pictorial Account of the Slums of Dublin in 1913. Dublin, IE: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 2008.

Crowe, Catríona. “Dublin 100 Years Ago: Death, Disease, and Overcrowding.” Fountain Resource Group. November 29, 2013. http://www.frg.ie/local-history/dublin-100-years-ago-death-disease-and-overcrowding/

Cullen, Frank. “The Provision of Working-And-Lower-Middle-Class Housing in the Late Nineteenth-Century Urban Ireland.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 111C (2011): 217-51.

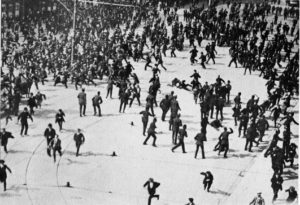

Devine, Francis, ed. A Capital in Conflict: Dublin City and the 1913 Lockout. Dublin, IE: Dublin City Council, 2013.

Moody, Janet. The Tenement Dwellers of Church Street, Dublin, 1911. Dublin, IE: Four Courts Press, 2017.

Prunty, Jacinta. Dublin Slums, 1800-1925: A Study in Urban Geography. Dublin, IE: Irish Academic Press, 2000.

ROBBY:

Brown, Terrance. Introduction. Dubliners, by James Joyce, the Penguin Group, 1992, pp. vii-xlviii.

“Crime in the slums: Appalling housing conditions at the root of many problems.” Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 17 May 1913.

Dawson, Charles. “The Dublin Housing Question,–Sanitary and Unsanitary.” Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 1913.

Luddy, Maria. “‘Abandoned Women and Bad Characters’: prostitution in nineteenth-century Ireland.” Women’s History Review, vol. 6, no. 4, 1997, pp. 485-503.

Kearns, Kevin C. Dublin Tenement Life: An Oral History. The Penguin Group, 2000, pp. 184-220.

Republic of Ireland. The National Archives of Ireland. Ireland in the early 20th century: Poverty and Health. Dublin: Republic of Ireland. Web. 9 Nov 2018.

“The Tenements.” History Ireland: Ireland’s History Magazine. Sept/Oct 2011: Volume 19. Web. 9 Nov 2018.

CATHRINE:

Primary Sources:

Skinnider, Margaret. 2016. Doing My Bit For Ireland (Illustrated Edition). S.l.: Echo Library.

Secondary Sources:

McGarry, Fearghal. 2017. The Rising: Ireland: Easter 1916. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wills, Clair. Dublin 1916 – the Siege of the Gpo. London: Profile Books, 2010.

Yeats, William Butler. “Cathleen ni Houlihan.” Plays in Prose and Verse, Macmillan Publishers, 1922, pp. 3-18.

LAUREN:

Primary Sources:

Hamilton, Norway. The Sinn Fein Rebellion as I was it.

Secondary Sources:

“1916 Easter Rising | 1916 Rebellion Ireland | GPO Dublin.” Patrick Pearse | Leaders of the 1916 Rising –, www.gpowitnesshistory.ie/1916-easter-rising/.

Metscher, P. (2001). The Easter Rising: A Critical Assessment. Nature, Society, and Thought, 14(1), 187-202. Retrieved from https://proxy.geneseo.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1618936167?accountid=11072

Wills, Clair. Dublin 1916: The Siege of the GPO. London, Profile Books, 2009.

JOEY:

Primary sources:

Pearse, Patrick. “Patrick Pearse’s Graveside Panegyric for O’Donovan Rossa on 1 August 1915 at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.” Easter Rising 1916 Ireland. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://www.easter1916.net/oration.htm.

Pearse, Patrick. “POBLACHT NA H-EIREANN THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC TO THE PEOPLE OF IRELAND.” Easter Rising 1916 Ireland. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://www.easter1916.net/proclamation.htm.

Connolly, James. “The Slums and the Trenches.” Modern History of the Arab Countries by Vladimir Borisovich Lutsky 1969. Accessed December 13, 2018. https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1916/02/slums.htm.

Secondary Sources:

CONNOLY, JAMES. LABOUR IN IRISH HISTORY. S.l.: CITIZEN PRESS, 2016.

Foy, Michael, and Brian Barton. The Easter Rising. Stroud: History Press, 2011.