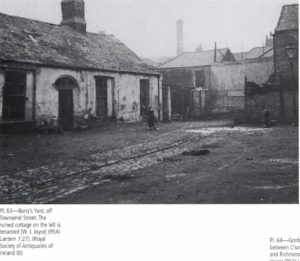

Notorious for inhumane conditions, Dublin’s tenement districts were “deemed the worst slums in Europe.” Tenement houses, while having been considered to be a necessary evil in the city due to the growing number of poorer citizens, were not always a major component to the urban landscape. Starting in 1801 with the enactment of the Act of Union, causing the dissolution of the Irish Parliament and the exodus of the upper class, the empty Georgian homes were converted into multiple family tenement-style housing for Dublin’s poorest populations. Once it became clear that the upper classes were not returning, their “houses purchased for £8,000 in 1791 were sold for a paltry £500 in the 1840s.” Low-income housing became the “solution” for the growing issue of lower-class homelessness and over-inundation within the population. Therefore, multiple styles of low-income

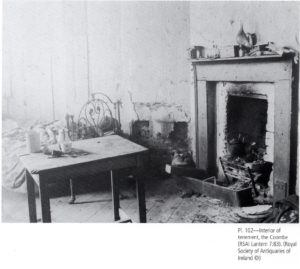

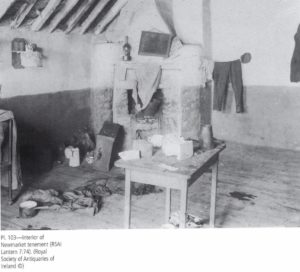

housing, such as “the tenement house, third class houses, and cellar dwellings” were found dotting the city. While all of these were not adequate choices for raising healthy families, the cellar dwelling was deemed to be the worst out of the three. Being that they were constructed underground, the rooms would perpetually be damp and cold, causing not only respiratory diseases and disorders, but also lacked a healthy amount of sunlight, meaning that smoke from the fireplace, used for cooking and for warmth, as well as candles, would be poorly ventilated. As Mary Conner remembered, “The ones down in the basement were the worst of all, they were stinking. Old people who had no one belonging to them alive lived in them. The people in the house overhead of them looked after them. It was poor looking after the poor…the worst place in a house people could live in as they were dark, cold, and moldy” This could cause disease to sprout and fester, and since the environment was not warm to begin with, overcoming illness became extremely difficult for all tenants, but especially for those who lived in cellar rooms.

Death and disease was an ever-present reality for those living in tenements. As the physical deterioration of the houses themselves, it became a breeding-ground for fatal diseases such as tuberculosis and cholera. The area around the tenement houses helped to foster the breeding of such fatal illnesses. Most tenements had small outdoor areas behind the building, but some of these areas were contaminated with “ manholes with sewage flowing out of them in the backyards where children played.” Many children that grew up in the tenements remembered how “the environment was littered with slaughter houses and piggeries while horses, cattle, and sheep were always being driven down the street. Animal dung was splattered in cobblestone crevices and bugs, vermin and rats infested every tenement house”

The bleakness of the situation continued to grow and fester up until the time of the Lockout in 1913. With the high unemployment and tensions between employers and employees running high, workers joined various labor unions in an attempt to protect their rights and their jobs. The most common working class union in Dublin was the ITGWU, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, led by James Larkin, a believer in using militant methods, such as the

sympathy strike, in order to secure the rights of unskilled workers, many of whom lived in the tenements. Larkin became a very popular figure for the working class, especially after the ITGWU had gained average wage increase of 25% earlier in 1913. On the other hand, William Martin Murphy, the primary employer for much of the working classes, owning not only the Irish Independent and the Evening Herald, but also was the head of the DUTC, or the Dublin United Trade Council, was adamantly anti-unionist. The Lockout thus began on August 15, 1913, when Murphy laid off 40 men and 20 boys from the Irish Independent’s delivery department when they refused to give up their membership to the ITGWU. On August 21, 100 tramway workers were faced with the same situation, leave the ITGWU or lose one’s job.

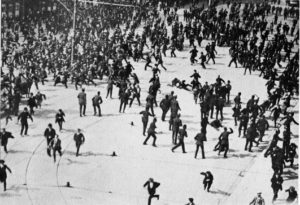

Essentially, Murphy was locking out working class men from their jobs due to their union membership. Conflicts ensued over the next few days, finally boiling over on August 30, when the police forces baton-charged on a riot that had formed, killing James Nolan and James Byrne. Then, on August 31, police charged on civilians walking home from Sunday Church, injuring over 600 people. Later that night, police stormed into working class tenements on Corporation Street, began to beat the tenants, going as far as beating “John MacDonagh, who was paralyzed…as he lay in his bed, and when his wife intervened, she too was beaten”, and destroy the few possessions the tenants owned, targeting religious items specifically.

Authors: Emily Meyer and Robby Billings