In other sections of this site we’ve analyzed in greater length some of our ideas behind how and why sport, art, community center, and school programs generate peace-building. But on this page we want to discuss a few of the ideas that led towards those observations and also some of the questions that this site hopes to prompt.

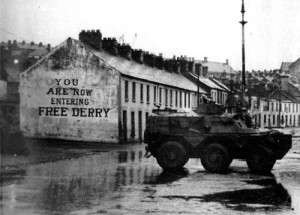

Subjectivity of Conflict

Theorist John W. Burton argues in his article Resolution of Conflict,

Conflict is essentially subjective. The traditional view is that while subjective elements are present, there is a dominating ‘objective’ conflict of interests. The traditional assumption is that there is a fixed amount of satisfaction to be shared in any given situation…the conclusion of conflict must be such that any gain in satisfaction by one side results in an equal loss to the other… Each [side] tends to rule out [the possibility of mutual satisfaction]…while admitting that the hypothesis may be valid in other conflicts. However, the fact that an essentially subjective relationship can be imagined in other cases is sufficient to cast doubt on the traditional notion of inevitable objective conflicts of interest. (10)

From this idea, we extrapolated that a major component of peace and reconciliation processes is that individuals recognize their own subject positions – the possibility that what they believe fully might not be inherently true, but rather be a perspective. Most of us, and as Burton claims even those involved in deep-rooted conflicts, often recognize this concept to be true in an abstract sense. But often we do not recognize it’s application to our own specific contexts and disagreements. As a result, we would argue that many of the projects we examine achieve their means by creating a ‘3rd space,’ a space that removes the context creating disagreement and instead places individuals in abstract spaces: sports, arts, schools, and community centers.

Artificiality

So why have people play sports together? Why have them go to theaters? Why make them sit down to talk in rooms painted bright, hopeful colors, or have them make art together?

We argue that one possible reason is that all of these spaces are ‘artificial’. By artificial we mean that the spaces create environments in which people interact with different rules and settings than they would in their daily lives. Therefore, these environments are not ‘real’ in a political or outside-world sense, but rather their focus on performance, role-playing, teamwork, and constructing something makes them abstractly real. As a result, it’s not the production of a play, or winning the game that matters, but rather the act of accomplishing something alongside others.

We argue that these projects generate shared experiences between people through the ‘3rd space’ they create – a space removed from reality. In effect, changing the ‘rules’ of how people interact, based on the rules of a game, or just the task of building something, creates scenarios and rules that are artificial in one sense, but also allow people to see how rules/laws/views, aren’t set in stone, but rather, depend on context. As a result, if individuals experience subjective relationships, which Burton argues individuals can often imagine in other spaces if not the one where they are in conflict, it is not a huge step to then recognize how subjective and context-dependent their conflicts may be too. Further, even if individuals continue to believe their own point to be right, acting in such a way that recognizes subjectivity, or role-plays it, becomes an act of healing. By ‘playing the part’ maybe one could come to believe that ‘part’ to be real, and live it.

Self-Reflection & Further Questions

In their work Peacebuilding: A Planning, Monitoring, and LearningToolkit, J.P. Lederach, Reina Neufeldt, and Hal Culbertson, state that in order to create a peacebuilding program organizers must have “a theory of change … an explanation of how and why a set of activities will bring about the changes a project’s designers seek to achieve” (25). Though we are not using a ‘theory of change’ to plan our own peacebuilding program, this site uses this idea of a theory of change to identify what the peacebuilding programs we examined are actually doing to create peace. These authors remind us that “in demystifying theory, it is important to remember that a theory of change is not an academic hypothesis, but rather an everyday expectation about ‘how the world works’” (25). This question, as to whether what we are doing here is purely offering an academic hypothesis, or if these ideas actually help viewers gain a better sense of ‘how the world works’ seems to be an important question to ask. The distance between ideas created in academic settings and the outside world may mimic the move that is made by these peace projects: an academic approach allows us to make revelations through an artificial space. How to convince doubters that these kinds of artificial spaces do matter and can make a difference poses a more challenging question than the ones we have tried to explore on this site. Thus, future research could be conducted on how to begin bridging this gap.

[Home Page][History & Background][The Ireland Funds][Organizations]