“The political direction of the army has been strictly neutral at all times between the Catholics and Protestants. […] Under no circumstances were we allowed to take sides […] Bloody Sunday ripped all that apart.”

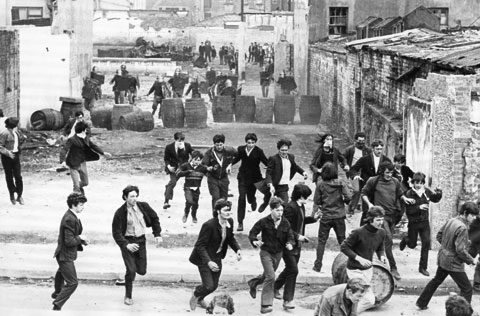

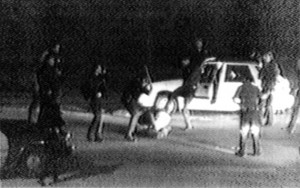

On January 30th, 1972, a peaceful protest and march took place in Derry, Northern Ireland. The protest (banned by the government because it was seen as a violent display) had thousands of attendees, estimated near enough to 6,000 people by the Widgery Report, the official response from England. The march began at about 2:00 PM, with the Catholic citizens marching through the Bogside, advocating for their rights. British Soldiers and Ulster officers “chaperoned” the protest, well armed. Soldiers had placed themselves along the walls surrounding Derry, with rifles poised and ready to be used if necessary. When the march reached its end, many in the crowd had grown angry and unruly at the presence of the British soldiers and Paratroopers (known for being particularly violent soldiers), and began to shout at them, calling them obscenities. A riot broke out, and the enforcement at the event responded, shooting into the crowds. By the end of the riot and response, 13 people were dead and 14 were wounded. A total of 108 rounds were fired.

Reports from Eyewitnesses that day all have the same consensus: the reaction from officers that day was overly violent, and the deaths that occurred that day were uncalled for and brutal. Collected and discussed here are seven eyewitness reports from Don Mullan’s Eyewitness Bloody Sunday.

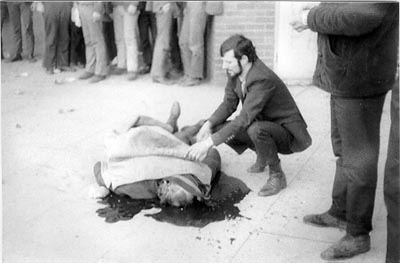

Patrick Joseph Fox was 38 years old on Bloody Sunday. He was trying to let people into his flat during the shootings in an attempt to keep them safe. He looked outside to see if anyone else needed help, and saw Fr. Daly kneeling beside someone (this someone was the dying Jackie Duddy, who was 17 years old), and wanted to go out and help him, if he could. Bullets were flying and someone ran in front of Fr. Daly, shouting “Don’t shoot Fr. Daly! Shoot me!” The man was then shot in the leg. Fox then went around to the front of his flat and saw four young men laying on the ground. He convinced them to come into the flat, but the fourth man got shot as he came in. Fox went to find help, but when he came back, the man had died. The man who had died was Michael Kelly, aged 17.

Bridget O’Reilly had not participated in the march that day, but she had headed to Rossville Street to see it. When tear gas was fired, she turned to go home, and had barely made it back before the shooting began. She managed to get some people into her house before she saw a man in Glenfada Park get shot. She got him carried into her house and went to find a priest, and when she came back, then man had died. The man was William McKinney, aged 27.

Raymond Rogan had also not participated in the march on January 30, but when he heard gunshots being fired, he look out his window and saw two men shot and dying on the ground. He opened his door to get them into his house, and when the were brought in, he saw the scope of their injuries. One of the men in the room, a doctor, told him that if the boy wasn’t brought to a hospital, he would die. They got him into a car, and drove in the direction of a hospital. They got stopped at a police blockade and were pulled from the car, and the car was driven away by one of the RUC members. He was detained under the Special Powers Act for an entire day, with the reason being that explosives were in the car. The young man in the back of the car, Gerard Donaghy, was said to have been found with nail bombs in his jacket pocket; he had bled out.

Peter McLaughlin was in his apartment when he heard gunfire. He looked out the window and saw several people laying on the ground, some injured and some not. He saw one injured man crawling towards the nearest building, when two shots were fired at him; the first missed, the second hit his side. The man yelled out “Ah! Christ, they shot me again” before dragging himself a few feet, then laid motionless upon the ground. He laid out on the ground for fifteen minutes before help was able to come, but he was already dead. His name was Patrick Doherty, and he was 31 years old.

Matthew McCallion had attended the march on Bloody Sunday, and he fled with Fr. Daly with the police started firing CS gas and rubber bullets. He was hiding in a building when he look out the window and saw “a fellow came out with a white flag, no sooner had he done this when the middle one of three British soldiers pulled the trigger and shot him in the head. I have witnessed this as God is my judge and I say it was cold blooded murder.” The man who was shot in the head was Bernard McGuigan, who had been going to the aid of Patrick Doherty.

Matthew McCallion had attended the march on Bloody Sunday, and he fled with Fr. Daly with the police started firing CS gas and rubber bullets. He was hiding in a building when he look out the window and saw “a fellow came out with a white flag, no sooner had he done this when the middle one of three British soldiers pulled the trigger and shot him in the head. I have witnessed this as God is my judge and I say it was cold blooded murder.” The man who was shot in the head was Bernard McGuigan, who had been going to the aid of Patrick Doherty.

Peter Kerr was in his house when he heard the sound of bullets being fired, followed by a few men carrying an injured young man towards his house. He brought them in, but the man died in the living room not long after his arrival. Kerr stresses that the young man, Michael Kelly, was not armed in any way. He checked on his children and, during a lull in the shooting, had another man brought into his home. He ran to get an ambulence when the firing picked up again and he took cover. When there was a pause, he went back to his home and got the two men into the ambulence. Kelly was dead, and the other, James Wray, was still alive, but looking very bad. Kerr, at the end of his report, states “At no time did I see any person or persons other than soldiers with firearms.” Wray did not make it to the hospital.

Michael Bridge was in the march on Bloody Sunday, and he was with a large group of people when the bullets started flying. After being bothered by the gas in the air, he turned down an alley, before fleeing. He tried multiple times to find a safe place to hid, and ended up getting hit with a rubber bullet once, and was shot in the leg with a round towards the end of the shooting. He noted, at one point that one of the paras had “his rifle on his shoulder in an aiming position. I noticed he did not have a riot visor down over his face. There was no camouflage paint on his face”, as though they knew that the protesters would not fight back.

Citations

- Mullan, Don. Eyewitness Bloody Sunday. Dublin: Wolfhound, 1997. 83-84, 117-119, 121-122, 127-129, 130-131, 133-135. Print.

- “The Victims of Bloody Sunday.” BBC News. Web. 10 Dec. 2014. <http://www.bbc.com/news/10138851#story-heading-3>.

Roadmap