While Patriot Games gained popularity for its action and excitement, its audience was shielded from historical accuracy and background. Patriot Games included little to no content of the Troubles, the IRA’s reasons for the violence depicted in the movie, and the unfair demands made by the British during the peace process. To Irish Republicans the IRA represented freedom and justice for their own land and leadership from the British.

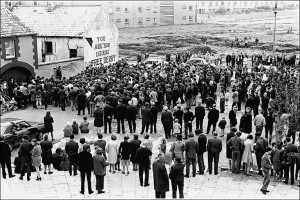

Similarly to Americans during the Great Revolution, Irish Republicans dreamt of becoming their own independent nation. Because the British were so uncompromising, the IRA had to resort to violence as a way to make their voice heard. While killing people in Northern Ireland with bombs and attacks against the British, the IRA sacrificed their own people which confuses outsiders and even people well-informed of the IRA. However, it has been a tactic for them as it is a common belief to supporters of the IRA that the “end justifies the means,” as Aoirghe from Eureka Street claims. (McLiam Wilson 293).

Patriot Games failed to incorporate the repression Irish Republicans experienced from the British Unionists in their own country causing the IRA to persist with their violence. Rather, Noyce focused on entertainment and dramatizing history by making the IRA the “bad guys.” The Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Patriot Games, consisting of characters Sean Miller, Kevin O’Donnell, and Annette portray them to be power-hungry and vicious.

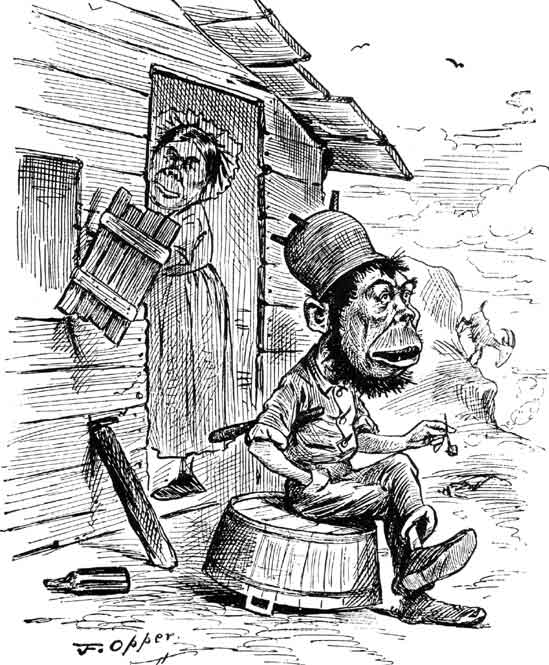

Similarly to the way Irish were depicted to the outside world for the past few hundred years, the IRA was depicted as inhumane in the photo below titled, “A King of Shanty” found in thesocietypages.com. The Irish were dehumanized for centuries as they were often compared to monkeys, apes, and in this caricature, an African American tribe who the artist perceived as little different from primates. Apes and monkeys were used to stereotype what the Irish were as a nationality because of the physical traits and mental capacities of what the primates were born with and those the Irish were perceived to utilize. Primates are physically unattractive with their bodies covered with dark hair and broad facial features and the Irish were perceived to the British as lazy and unkempt. This comparison was used widely by Americans and the British because of Britain’s oppressive influence over Ireland. This parallels Patriot Games’ depiction of the IRA as the movie dehumanizes the physical traits of Sean Miller, a member of the IRA. Of the multiple visual insights included in Patriot Games to depict the IRA as villainous, one that particularly stood out showed bloodshot eyes of Sean Miller at 2:27.

Along with the visual insights depicting the IRA as inhumane, movie reviews also depicted them as inhumane through diction. Rottentomatoes used the term “neutralize” while reviewing the movie. This indicates the subject of the matter to be wild and undomesticated as they need to be tamed. Also, the method of taming is unnatural, implying that a natural force is not strong enough to contain the disruption. Rottentomatoes also wrote of Sean Miller to exhume “the wrath of a maniacal Irish radical,” which states he has an unstable mental state.

Along with Rotten Tomatoes, New York Times’s critic Janet Maslin acknowledges Patriot Games’ portrayal of Irish Republican Army to be the “bad guys.” (Rottentomatoes 1992).This is evident as she wrote, “On the other stand Irish terrorists who, in the absence of the kinds of cold-war villains who populated Mr. Clancy’s “Hunt for Red October,” are the author’s best exemplars of the forces of anarchy and evil.” Tom Clancy, the author of Patriot Games, is well known for his action thriller novels and because each novel of this sort needs a protagonist, he had to exaggerate the actions and means of the IRA.

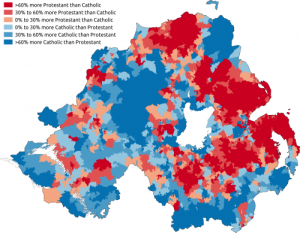

Maslin is better-informed of historical background of Northern Ireland as her review shows. Unlike the critic of Rotten Tomatoes, she gave mention to Patriot Games’ diversion from historical accuracy of the IRA. (Rottentomatoes 1992). She wrote, “The Queen of England owes a debt of gratitude to the makers of “Patriot Games,” the sleek film adaptation of Tom Clancy’s best-selling paranoid thriller,” which provides readers with her knowledge of tension between the British and the Irish or rather the Protestants and Catholics. In both reviews critics (who represent the audience) project what they perceive the movie to be to Americans who in turn read and if little knowledgeable of the Irish Republican Army, will believe the review and the situation to be reality.

Irish Echo, the oldest and most widely read American-Irish newspaper in the United States, dug deep into the novel that this film is based on. Identifying that the IRA were portrayed in the film as “crazy, bloodthirsty Irish terrorists stalking suave and civilized British royalty” (O’Hanlon 16 Feb 2014), O’Hanlon, the author of the article, made it apparent that there was a great misrepresentation felt by the Irish-American citizens in the United States.

However, O’Hanlon does not totally blame Clancy for this misrepresentation, as he acknowledges that “Movies, of course, don’t always fully reflect the books they are based on and that may have been the reason why Clancy more or less escaped the widespread annoyance felt by Irish and Irish Americans alike over the way that different nationalities were portrayed in the movie.

Although Clancy may not have intended for the IRA to look and feel as vicious as they did in the movie, the fact that the IRA was so monstrous only plays into the idea that Hollywood is willing to exaggerate history to make for a more thrilling drama. Director Phillip Noyce included the ugly nature of the IRA, the killing and bombings, without giving them a proper purpose in the film. This depiction of the IRA, as a blood-thirsty organization, is a great misrepresentation felt by movie critics, Irish and American, across the United States.