The Troubles erected peace lines through Northern Ireland, creating a divide between Catholics and Protestants. Two distinct occurrences that detail the change in the social and political climate of Northern Ireland during the Troubles are murals and the loyalist parades (If you are intrigued by the murals and their presence in Irish culture you can click [here] to see Jade Chang’s article on that topic). Parades were organized by the Loyal Orders, an organization made to celebrate and defend Loyalist (British) traditions in Northern Ireland. Popular organizations of this Order are the Orange Order, Royal Black Institute, and the Apprentice Boys, the Orange Order being the most popular of the groups. There are multiple sects of the Orange Order based on status, gender, and age, so it really encompasses all Loyalist demographics (1).

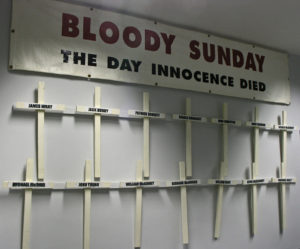

With the task of preserving loyalist ideals, the Orange parades occur during anniversaries of Protestant victories over Catholics in skirmishes through both England and Ireland. Even though Nationalists have a history of participating and organizing parades like Loyalists, this tradition petered out and became a Loyalist custom. Loyalists used this thought process to their advantage and began to use things like marching bands to accompany music to the parades, adding “spectacle” for Loyalists and an intimidation tactic for the “other” community (2). Orange parades even went across the peace line barriers into Catholic territory so the people of the Catholic faith would have to witness the Protestant agenda, which lead to a lot of friction between groups. Fed up with the conditions Catholics were forced to endure, they turned to civil rights marches. These marches were made illegal in the eyes of Northern Ireland’s government soon after bringing more outrage since Orange parades were still permitted. In defiance to these injustices, Catholics organized marches for their natural born rights without regard for the law, leading to tragedies like [Bloody Sunday] (read more about this on Eamon’s page describing this massacre). This showing the dynamic between Protestants and Catholics quite well, with Loyalists being about an uprising so they responded to small infractions with big actions and Nationalists just desperate to have their voices to be heard while being continually silenced until violence broke out amongst sides.

These parades have not ended and have maintained an air of tension between Catholics and Protestant due to the background and context of them. Celebrating these events each year bringing a sense of tradition but also stubbornness, Loyalists partaking partially just to show Nationalists they are still able to go through with these parades. At a certain point you have to wonder how fun these parades are to watch due to the fact that there are 9 foot walls erected between the spectator and the parade out of the fear of the bomb threats and bombings the parades have seen throughout the past (3). The only resistance people have to stopping these practices are that it interrupts tradition and erases history, reminding me of the current debate in the United States over the destruction of confederate statues. Even though these confederate statues symbolize slavery and are sending horrible messages to the African American community, people are still attached to them due to the historical significance. However, there is a thin line when appreciating historical landmarks. Just because something is old, it shouldn’t mean people can glorify old ways that won’t work in this time and age, especially within cities such as Belfast because each mural, memorial, and event of commemoration seems to only show a biased view of their history. Not giving a truthful outlook on the wrongs both sides carried out on the other side of these peace lines. The effects these parades have on societal issues in the current climate are still unhealthy and are stunting the growth of their culture. Both Nationalist and Loyalist sides of Northern Ireland are still spiteful and passive aggressive, forming an unwelcome standard for the new generation to adhere to. When Northern Ireland partakes in these biased commemorations like the parades, it indoctrinates the youth with the same aggressive thoughts that could lead to another conflict later on. This ideology being akin to our page, [Borders, Boundaries, and their Function in Northern Irish History], discussing the social boundary between the Nationalists and Loyalists that erects physical borders and political stigmas. This then creates more social boundaries and so on and so forth as each generation gets dragged in until boundaries can be resolved and borders can be brought down.

You can return to our main page [here] also check out Carina’s post on the Belfast Agreement [Here]

This video below shows the type of unrest between Nationalist and Loyalists during the parades.

Citations:

(1) Mcatackney, Laura. “Memorials and Marching: Archaeological Insights into Segregation in Contemporary Northern Ireland.” Historical Archaeology 49, Page 118

(2) Mcatackney, Laura. “Memorials and Marching: Archaeological Insights into Segregation in Contemporary Northern Ireland.” Historical Archaeology 49, Page 119

(3) Mcatackney, Laura. “Memorials and Marching: Archaeological Insights into Segregation in Contemporary Northern Ireland.” Historical Archaeology 49, Page 122

The parade and the general celebration of St. Patrick’s day was used as a way to celebrate Irish-American identity. At one point it was even the most popular ethnic celebration in America and helped develop

The parade and the general celebration of St. Patrick’s day was used as a way to celebrate Irish-American identity. At one point it was even the most popular ethnic celebration in America and helped develop