“Quite honestly I owned the Bogside in military terms. I occupied it.”(1)- Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford, Commander of the 1st Paras.

The Walls of Derry have a long history of dividing Catholics from Protestants. In fact, since their construction in the early 1600s, the Walls have formed a hard boundary between the two. Built by Protestant settlers, the Walls functioned to protect the lives and property of the transplants from the colonized Irish Catholics living in the marshlands beyond, the area that would later come to be known as the Bogside (2). When the Protestant settlers within successfully withstood a siege by Catholic forces loyal to King James II between 1688 and 1689 the Walls gained a symbolic weight previously not present. Thereafter they were a clear source of pride for the Protestants and one of repression for the Catholics outside.

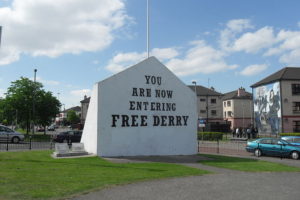

Following Partition in 1920, the situation of Catholics in Derry deteriorated. Despite a growing population, by 1972 33,000 of the city’s 55,000 people lived in the Catholic districts of Creggan and the Bogside (3), successful gerrymandering ensured Protestant rule over the Catholics. In August, 1969, an Apprentice Boys March past a major entrance to the Bogside triggered a three day clash between police and Catholic demonstrates. Political and social turmoil culminated when the inhabitants of the Bogside and Creggan defiantly walled themselves off from the remainder of the city using burned out cars, concrete slabs, old bed frames, rubble, and anything else at hand (4). A city famous for its Walls had seen a second set of fortifications erected. The Protestant population once besieged now found itself in the position of the besieger, and the Catholic majority found itself encircled in a sea of Protestant orange. Further, the social and cultural boundaries that had long existed in the city were turned into a hard border between Catholic and Protestant.

“Derry/Londonderry is a place where walls and barricades, borders and boundaries- both material and symbolic- have defined political and social life throughout its 400 year modern history.”(5)

On January 30th, 1972, British Army forces used an anti-internment march in the Bogside as an excuse to tear tear down these borders and reclaim control. The erection of borders is always a statement of power, an assertion of the ability to control movement of people, similarly the deconstruction of borders is a clear declaration of strength. On that day, British forces effectively stormed the “walls” of Creggan and Bogside and bloodily ended the second siege of Derry.

The vanguard for the British reconquest was the elite 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment, a unit only recently arrived in Northern Ireland from operations in the Mediterranean. These were not troops for standard anti-riot detail. They stood apart from the British infantry that many in Northern Ireland had grown accustomed to seeing. Many wore distinctive red berets and camouflage smocks, few wore riot gear. (6) It seemed clear the Paras, as they were known, were not here to keep the peace. For the thousands gathered for the march, it soon became clear the Paras intent was the furthest thing from peaceful.

The first real sign of trouble came when the march came to the junction of Rossville and William Streets. Here, about 200 of the protestors strayed from the main body to pelt the guards at the barricade there with stones. However they were soon repelled with rubber bullets and water cannon. (7) Paras stationed around the Presbyterian Church on William Street soon dispensed with rubber bullets though. It was here that the first live high-velocity rounds were fired, 15 year old Damien Donaghy, the first shot, a non-lethal wound to the hip.(8) He was the first of 26 shot that day, 13 of which died that day, followed by a 14th a year finally succumbing to his wounds.

As the primary goal of the British operation that day was to forcibly reassert control over Creggan and the Bogside, overt violence was viewed as a valuable means of achieving this. Having stopped the marchers at the barricades and keeping them from crossing the border into the city center, the Paras went on the offensive and invaded the Catholic portion of Derry. Though the assault lasted only a half hour, that 30 minute span has been seared into the memories of those who survived the attacks and witnessed the carnage. The second siege of Derry which had begun with a defiant and unlikely erection of a border by a weaker group, ended with a hail of gunfire and the storming of that border. Specific incidents like the shootings of Jack Duddy and at Glenfada Park potently emphasize the lopsidedness of the power dynamics at play. Bloody Sunday is perhaps the most well known of a number of attacks by both Catholic and Protestant forces that would stretch right up to the Good Friday Agreement.

.

- Jane Winter in Eyewitness Bloody Sunday , edited by Don Mullan, Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1997, pp. 29.

- Graham Dawson, “Trauma, Place, and the Politics of Memory: Bloody Sunday, Derry, 1972-2004.” History Workshop Journal 59 (2005): 151-78, pp. 158.

- Winter, Eyewitness, pp. 14

- Peter Pringle, and Philip Jacobson, Those Are Real Bullets: Bloody Sunday, Derry 1972, New York: Grove Press, 2001, pp. 35.

- Dawson, “Trauma, Place, and the Politics of Memory”, pp. 157.

- Pringle and Jacobson, Those Are Real Bullets, pp. 96-97

- Don Mullan, Eyewitness, pp. 17.

- Pringle and Jacobson, Those Are Real Bullets, pp. 113-115

Figure 4:

Figure 4: